This article contains extended allusions to scenes of sexual violence.

In 2011 the Royal Shakespeare Company revived Peter Weiss’ controversial play Marat/Sade. The first half culminated in a graphic orgy scene where the actors simulated sex acts until suddenly it became clear that one of the characters was no longer enjoying himself and a sexual assault was taking place. At length the scene ended and everything slowed to a haunting silence as the victim made his painful way off stage and then — bam! Lights down and time to head out for the interval.

Dozens of audience members decided not to come back.

The front row in particular was almost empty. The play was being staged in The Swan (probably my favourite theatre in the world) which has a ‘thrust’ stage: it sticks out into the audience who are seated on three sides of the rectangle so the front row is extremely close to the action. I remember counting myself lucky that the free ticket I’d got from a friend was up ‘in the gods’ at the top of the theatre. It was handy to be able to lean back and obscure my view of the stage for parts of the scene in question.

It was, unsurprisingly, one of the most walked-out of plays in the history of the RSC.

The Context

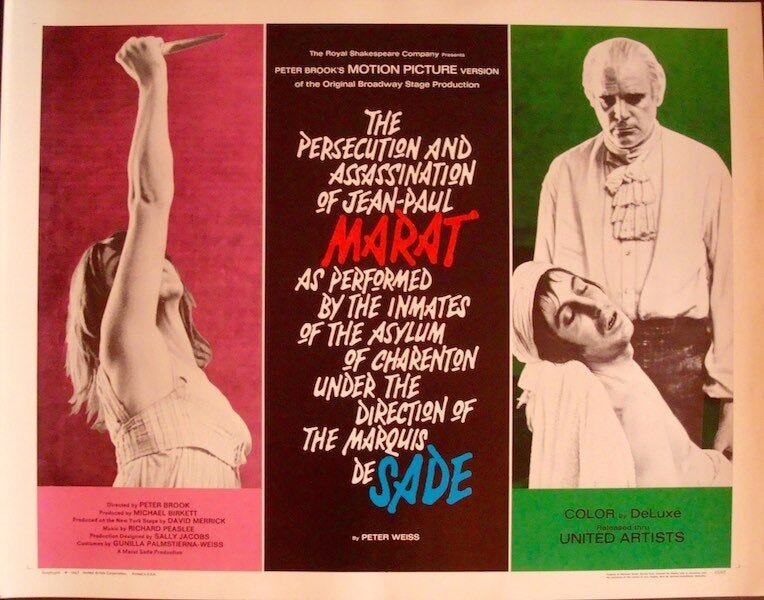

Marat/Sade premiered in 1963 with ground-breaking director Peter Brook at the helm. Some audience members did walk out then, but it won the Tony Award for Best Play and was hailed as a subversive masterpiece. The full 1967 film adaptation starring many of the original cast is on YouTube and I recommend it — I actually think Marat/Sade is one of the most interesting pieces of theatre ever produced.

So what’s it about? I’ll try my best but it is a bit complicated. Basically it’s set in a lunatic asylum not long after the events of the French Revolution. The Marquis de Sade has been confined there and he’s passing his time writing plays for his more capable fellow inmates to perform. This really happened, by the way, an early version of we call occupational therapy with a dubious degree of oversight from the doctors and wardens.

What we watch is a fictional account of one of these performances. Sade is obsessed with the revolutionary leader Jean-Paul Marat who represents an idealism that Sade is fascinated by and contemptuous of in equal measure. Since the real Marat was assassinated, Sade never got to have a proper argument with him, so he’s written one. An inmate undergoing hydrotherapy plays Marat who spends the play pontificating from his bathtub, like the real Marat who had a painful skin condition and was murdered in his bath.

An inmate with narcolepsy plays the real-life assassin Charlotte Corday who, for complicated political reasons, has decided that Marat needs to die so that France can heal. She has some of the most breathtaking moments in the play, and often collapses in a narcoleptic stupor after a great speech. It’s a play within a play where the line between the real-world lunacy of the Revolution and the unwellness of the inmates is never clear. It’s a challenge for the actors who are always playing two characters, and a test of an audience when things get increasingly out of hand.

Oh and it’s basically a musical, a lot of the story is told through song.

The 2011 Production

There are plenty or reasons to find the original Marat/Sade challenging. There’s a lot of violence, sexuality, and nihilism in the story itself, and it requires actors to pretend to have an array of mental and physical afflictions — something that is increasingly frowned upon as theatre renegotiates its relationship with disability. Yet surely people coming to see the play in 2011 knew enough about its history, or at least had heard the name ‘Sade,’ and understood what was on its way?

The odd thing about the 2011 production was that the upsetting scene I described at the opening of this article was an addition to the original script. There is a final climactic scene where order breaks down and the inmates rule the asylum, but the play doesn’t have an orgy-turned-sexual-assault halfway through, in fact this winking piece of metatheatricality is how the herald sends the audience out to the interval:

When I afterwards learned that this scene had been changed it helped me put my finger on exactly why it felt gratuitous. The last thing the audience had seen before the interval was the victim trembling as they stumbled offstage, but when we returned the rest of the play carried on with no indications from anyone that the assault had taken place. Because it wasn’t in the script, it was entirely emotionally unaccounted for, our lingering horror made it hard to get back into the play’s political to-ings and fro-ings. You felt like screaming “Stop pontificating about democracy, you two — is that guy at the back okay?”

Living with the Pain

The 2011 Marat/Sade forms an interesting point of contrast with another shocking production staged three years later in 2014, this time at The Globe. This was Lucy Bailey’s brutal interpretation of Titus Andronicus, a play so violent and disturbing that it formed four of the ten articles in my ‘horror moments’ series on Shakespeare. Bailey didn’t hold back on the gore and, to my knowledge, it still holds the theatre’s record for the most faintings and walk-outs of any production.

Titus is a grim revenge drama which has a particularly nasty sexual assault at roughly the halfway mark. It’s arguably much worse than the one previously described because the victim is grotesquely mutilated and we have to live with the sight of her in bandages for most of the rest of the play.

That’s the thing though, we have to live with her.

In my opinion, the greatest and most affecting depictions of violence are those that centre the humanity of the victim. Lavinia isn’t just a spare body there to provide shocks, she’s a person and remains a person after her ordeal. My favourite line in the play is Titus’ reply to being told ‘this was thy daughter.’ He corrects it as he cradles her: ‘that she is.’ (My article on Lavinia is here.)

The 2011 Marat/Sade didn’t seem to be entirely in control of what it wanted its audience to feel. Critic Michael Billington described it as ‘Artaud for Artaud’s sake’ which is a theatre-person way of saying ‘needlessly cruel.’ Because of that cruelty, I’m not even talking about the production’s new political statements for a twenty first century audience, I struggle to remember those adjustments in detail though I can see from reviews that they were there. It’s hard to pay attention to cerebral and satirical nuance when you’ve just been mildly traumatised and that trauma is totally unresolved. There’s a time for being needfully cruel in storytelling, but if you don’t get the balance right, you lose people who would otherwise have listened.

Walking Out

I’m a big believer in the right to walk out, although I rarely do so myself. Now that I think about it, I’ve only ever walked out of a theatre once from a perfectly PG musical adaptation of a novel I love which was genuinely so ear-scraping and misjudged that I needed to escape. (If I ever get a bestseller badge, maybe I’ll reveal which novel it was to paid subscribers. I guarantee that you’ll all say ‘they tried to make a musical out of that?’)

I stuck with the 2011 Marat/Sade in part to see whether it was going to do anything clever with the aftermath of that pre-interval scene. If there had been a compelling consequence to it, the people who’d left behind those rows and rows of empty chairs would have missed out — but I wasn’t having a good time and it kind of spoiled the whole experience. It felt not only dramatically unsatisfying, but honestly kind of leery. I went home and watched the Peter Brook version and was astonished at how much more I liked it, how many speeches I’d barely registered now stuck with me for all the right reasons.

I don’t believe in theatre censorship: great art sometimes demands the inclusion of challenging images and upsetting scenes. Theatremakers should be able to put anything they like on stage as long as nobody is actually being physically hurt. But audiences must have the same freedom to say ‘no’.

Consent is at the heart of the relationship between a storyteller and their audience, and consent can be withdrawn at any time. Artists sometimes forget this dynamic, but I believe in it passionately. As a playwright and author I’m not entitled to anyone’s time and attention, and if something I’ve written makes them uncomfortable for any reason, they should be totally free to leave, no social pressure, no questions asked. Maybe I think they’re being a prude or a bigot, maybe it’s a shame they didn’t stick around to see where I was going, but you can’t demand consent. People walked out of the 2014 Titus Andronicus in droves, even though I personally think that that play gets better the more unflinchingly a director confronts its pivotal scene of sexual violence.

In the end, it doesn’t matter whether or not any one particular production gets its interpretation of a text right. What matters is that, unlike the poor characters, their audience members are allowed to leave. So don’t be embarrassed next time you wonder ‘should I walk out of this film/play?’ the answer is: I cannot tell you, it’s your sacred right to choose.

Have you ever walked out of a play or film? What made you leave?

Subscribe for more articles on a range of fascinating subjects. I publish my ‘horror moments’ on Thursdays, and other curious articles like this on Mondays.

Enjoyed this article? Remember that you can pay to subscribe for extra benefits or buy me a coffee here to keep me writing. You can also like, share, comment, and recommend to help the substack grow. Thank you!

Almost every play I've ever wanted to walk out of has been a community theatre production in which I've known at least a couple of the actors, and at that point, social nicety demands that I suffer through and then try to say something complimentary at the end which is not a lie (usually something along the lines of, "Wow, you all work so hard on this!")

The sole professional production I've wanted to walk out of was the Broadway musical version of Moulin Rouge, a play which seems to have entirely missed the point of the original movie. I stayed because the tickets hadn't been cheap, and we hoped the second half would redeem itself (spoiler alert: it did not).

Many, many years ago I worked as a theatre critic for the local newspaper (imagine a time when that was a thing!) and ached to walk out of quite a lot of dreadful productions, but of course I never could. I don't remember longing to leave out of disgust or horror, but certainly from boredom at stilted productions and particularly bad comedies. A night at the theatre can go on for a very long time when a creakingly unfunny farce is in progress.

I do now leave if I'm really not enjoying a play, although I'm usually too engaged (or at least interested) to want to leave. Nothing feels more liberating than walking away from something you don't have to sit through any more!