Extreme Horror - What happens to Lavinia in Titus Andronicus

Horror Moments, Shakespeare Edition

[Spoilers: Titus Andronicus (1592), The Virgin Spring (1960), Saved (1965), The Last House on the Left (1974)]

“To avoid fainting, keep repeating, 'It's only a play… only a play… only a play”

Last week I introduced Shakespeare’s goriest play, Titus Andronicus, and we left Tamora, Queen of the Goths — who had just watched her son being dragged away to be ritually disembowelled — vowing vengeance against Titus and all his family.

This week, we arrive at one of the most shocking scenes not only in Shakespeare but in the history of theatre: the rape and mutilation of Lavinia. If you’re in any way sensitive to themes of sexual violence, give this one a miss.

In Act II scene ii, Titus’ daughter Lavinia has ended up alone in the woods with Tamora and her two remaining sons, Chiron and Demetrius. When she realises she is about to be attacked she turns to Tamora and begs her to show pity as a fellow woman. Tamora’s touchiness here, telling them ‘I will not hear her speak; away with her,’ as the younger woman clings to her legs, betrays the discomfort of a troubled conscience, and we feel as if there might be hope that she’ll call off her sons.

But Lavinia makes a terrible mistake. She tells Tamora that she ought to grateful that her father spared her life when she was brought to Rome as a captive:

LAVINIA

O, let me teach thee! for my father's sake,

That gave thee life, when well he might have

slain thee,

Be not obdurate, open thy deaf ears.

Unthinkingly, Lavinia has brought back to mind the sacrificial murder of Alarbus. Tamora has not forgotten her grief about what happened to her eldest boy, and by mentioning Titus, Lavinia has sealed her fate. We can hear the queen’s heart hardening as she returns:

TAMORA

Hadst thou in person ne'er offended me,

Even for his sake am I pitiless.

Remember, boys, I pour'd forth tears in vain,

To save your brother from the sacrifice;

But fierce Andronicus would not relent;

Therefore, away with her, and use her as you will,

The worse to her, the better loved of me.

Lavinia now realises that she’s doomed one way or another, and so she begs for a quick death and to be spared from rape. Tamora spits:

TAMORA

So should I rob my sweet sons of their fee:

No, let them satisfy their lust on thee.

In my recent article on eye gouging in King Lear I touched on some of the subgenres of screen and stage that have been infamous for their graphic and sexualised violence, from the Grand-Guignol performances in mid-twentieth century France, to ‘torture porn’ films like Hostel in the early 2000s.

All of these raise questions about taste and censorship as well as the moral responsibility of a storyteller towards their audience. When should a camera cut away or a scene be taken off stage? How does watching violence affect the viewer? Is there a moral, artistic or philosophical justification for showing extreme images, or is it always titillation?

When I wrote about Gloucester’s torture in King Lear, I mentioned the fact that, for me, a huge part of the equation is how the victim is treated by their respective story. I mentioned late twentieth century playwrights like Sarah Kane and Edward Bond who took suffering seriously: both writers were heavily influenced by Shakespeare’s use of violence and both were criticised for their extreme gore.

Bond’s most famous play, for example, Saved (1965), gained notoriety for a scene in which a gang of teenagers stone a baby to death in its pram. It was censored by the Lord Chamberlain’s office, but the Royal Court Theatre defended it so staunchly that the case helped overturn theatre censorship for good with the Theatres Act of 1968.

Bond was a deeply political, socially conscious playwright who believed in the power of theatre to reveal uncomfortable truths. He had survived the Blitz and drew a parallel between the treatment of the infant by the young South London thugs, and the wars enacted by adults that had likewise taken innocent lives. The baby’s death is central to the play and we live with the consequences of this brutality which is not merely shock for shock’s sake, but the thematic fulcrum of the story. The Guardian’s critic Philip Hope-Wallace downplayed the novelty of this sort of imagery: ‘no more horrible than some episodes in Titus Andronicus.’

So what exactly happens to Lavinia, and how does Shakespeare depict it?

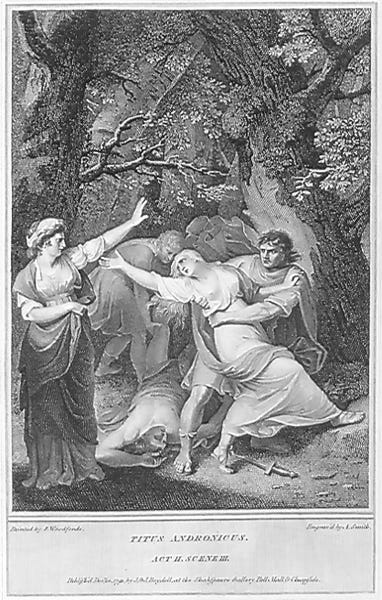

We find out in Act II scene iv when she is dragged back on stage by Chiron and Demetrius who seem drunk on cruelty, mocking the mutilations they have carried out:

Enter DEMETRIUS and CHIRON with LAVINIA, ravished; her hands cut off, and her tongue cut out

DEMETRIUS

So, now go tell, an if thy tongue can speak,

Who 'twas that cut thy tongue and ravish'd thee.CHIRON

Write down thy mind, bewray thy meaning so,

An if thy stumps will let thee play the scribe.DEMETRIUS

See, how with signs and tokens she can scrowl.

CHIRON

Go home, call for sweet water, wash thy hands.

DEMETRIUS

She hath no tongue to call, nor hands to wash;

And so let's leave her to her silent walks.CHIRON

An 'twere my case, I should go hang myself.

DEMETRIUS

If thou hadst hands to help thee knit the cord.

Exeunt DEMETRIUS and CHIRON

Even the idea that she can’t ‘knit’ a rope to hang herself because they’ve cut off her hands is hilarious to them.

This is the scene which made one of my friends faint when she went to see it at The Globe. It was, in fact, the same 2006 Lucy Bailey production (revived in 2014) that caused a record number of faintings and walk-outs. Bailey’s production refused to shy away from the reality of gore and blood, substituting graphic effects for the streaming red ribbons of more stylised stagings of the play. It was a powerfully tough watch.

In 1972 director Wes Craven made an infamous film called The Last House on the Left. It revolves around the rape and torture of two teenage girls which is depicted in groundbreakingly lurid detail, its famous tagline was: “To avoid fainting, keep repeating, 'It's only a movie… only a movie… only a movie.”

Although it took its basic plot from the stylish Ingmar Bergman film The Virgin Spring (1960), Last House forced the reader to watch far more of the violence than was (and is) conventional in film. It was caught up in the video nasties scandal and even sparked protests because of its supposed depravity.

Both Last House and The Virgin Spring are revenge stories which culminate in the parents of the victims committing shocking acts of brutality against the original perpetrators.

At a metanarrative level, the filmmakers are showing the viewer horrible violence in order draw them in as close as possible to the perspective of the vengeful parents. Having witnessed the original crime in all is horror we are far more intimately implicated in the sickly pleasure of retribution. Suddenly, we too want to see flesh sliced and blood spilt precisely because we empathised with the victim of the original atrocity. Arguably, such stories can only make this criticism of us if the acts of violence are as realistic as possible. Craven is only driving this point home with fuller force than Bergman.

Early modern revenge dramas understood this compromising dynamic so well that they often managed to play the trick several times within one story. Remember how thoroughly the audience empathised with Tamora when she was reduced to grovelling to save the life of her eldest child? Now she and her remaining sons have become the perpetrators of so vicious a vengeance that we are forced to reckon with the consequences of a hatred we have shared.

And we’re only halfway through the play! What next? Are we about to side with Titus again? Do we want something horrible to happen to Tamora, Chiron and Demetrius, and will that happen? When will it all end and is resolution of any kind at all possible now?

There are two more horror moments left from this play so we will see.

Before I go though, we can’t leave Lavinia lying there, handless and tongueless in the forest on her own, because Shakespeare doesn’t do this either. Unlike the girls in both of the films I’ve mentioned, or the poor baby in Saved, she is not murdered but survives her ordeal. Her uncle Marcus finds her and scoops her up. He takes her to her father and lays her broken body down before him. Incapable of reconciling the mangled bloodied mess with the image of his niece he says to Titus

MARCUS ANDRONICUS

This was thy daughter.

And then Titus has a line that always makes me teary. It’s very simple, but it’s the true sentiment that some of the goriest stories, despite their sensationalist trappings, are actually driving at:

TITUS ANDRONICUS

Why, Marcus, so she is.

She is his daughter. Always. Hurt, but human. No less Lavinia than she was before. And once they’ve all figured out a way for her to communicate the names of the people who did this to her, they’re going to think of something even worse to do in return.

Until next time, happy nightmares everyone.

Special thanks today go to my newest paid subscriber Bob Deis who co-edits Men’s Adventure Quarterly which reprints classic stories and artwork from men's adventure magazines that feature flying saucers, including several that are historically significant in the realm of Ufology. Issue #11 is currently available, so if you like pulp culture and UFO history do check it out, it’s lots of fun and beautifully presented. If you want to support my work with a paid subscription, do let me know if there’s anything you’d like me to give a shout out for in a future article.

Horror moments are posted every Thursday and a wide variety of articles exploring the history of magic, theatre, storytelling, and more are published on Monday afternoons.

So powerful. I firmly believe that the uncomfortable truths need to be explored, and that shock, violence or abuse should only ever take place as part of the story. Actually seeing the horror is a great way of describing the offending characters without describing them, if you know what I mean. What they're capable of is one thing... But then if you show what they're willing to do and what they actually do, you've emphasised to the reader what kind of character they are. You've shown them. That one scene can speak a thousand words, and leave people reflecting on it for months. As hard as it was for audiences to cope with that, drawing the curtain on certain scenes isn't always helpful. Not everybody will fill that gap with their imagination and let that be that. I'd forgotten about Lavinia putting her foot in it 😱

I've never been more affected by film scene than the scene in the 1999 adaptation where Lavinia slowly turns to towards the camera after the attack. Utterly crippling. I cannot begin to imagine the impact of the recent Globe version of the play you went to. Thanks for this nuanced view on one of the most horrific scenes of violence depicted in art.