Jack the Ripper Sings – Lulu/The Women of Whitechapel

Horror Moments, Opera Edition

‘Horror Moments’ is a weekly series examining horror-inflected scenes and themes in unexpected places. The ‘moments’ are published weekly on Thursdays, and I share articles on the history of magic, theatre, storytelling, and more on Mondays. Catch up with the recent Kate Bush series here and the full back catalogue of horror moments (from Wallace & Gromit to Shakespeare) here. Don’t forget to subscribe!

How do you tell the story of a serial killer through music?1

When I was growing up we had in our house a copy of the great tome ‘The New Kobbé's Complete Opera Book.’ It’s an encyclopaedia containing the main plots, roles, and a brief performance history of the most famous operas of all time. You could pick a title, flick to the entry and within ten minutes have a solid overview of everything except the music.

Since a lot of operas have absolutely outrageous stories, it was also essentially a collection of salacious plot summaries and had a similar appeal to surfing Wikipedia for descriptions of horror films you’re a bit too scared to watch.

Long before I’d ever been to an opera, I’d read about what happened in hundreds and had been particularly struck by a fleeting entry on an opera called Lulu for the simple reason that, astonishingly, one of the listed characters was ‘Jack the Ripper.’

Lulu

Lulu was written by Alban Berg (1885-1935) and premiered in 1937. It follows the downfall of the eponymous heroine who ends up working as a street prostitute in London and is murdered by, you guessed it, the Ripper himself. So far, so cliched: a cautionary tale of a fallen woman. But it turns out Lulu is a much more radical story than it first appears.

The story is fused together from two works by the great German playwright Frank Wedekind: Erdgeist or ‘Earth Spirit’ (1895) and Die Büchse der Pandora, or ‘Pandora’s Box’ (1902). Kadidja Wedekind, Frank’s daughter, combined the two into Lulu: A Tragedy in 5 Acts with a Prologue (1950).

For Wedekind, who was keenly fascinated with human sexuality, the ‘box’ of ‘Pandora’s Box’ was a deliberately lewd double entendre. Lulu’s vagina and womb are the central fascinations of the story which ends with their desecration by the murderer (the real Jack the Ripper removed reproductive tissue from some of his victims). Lulu’s life is one of extremes, of a sharp rise and a sharp decline, and Wedekind is fascinated by the way that male projections of desire shape this destiny. Interestingly, the most sympathetic character is the lesbian Countess Geschwitz whose pure love for Lulu makes her, according to Wedekind, the real tragic protagonist. She wants to study law specifically to help advance the cause of women’s rights, and after what happens to her and Lulu at the hands of numerous men, the story seems to impress upon its audience the necessity of this ambition.

So this is the play that composer Alban Berg was so intrigued by and which he began working to turn into an opera. But there was problem with the plan to stage the final opera in Berlin: the year was 1934. This was not a friendly climate for experimental, socially progressive stories with sympathetic prostitutes and lesbian women’s rights campaigners. When a version of the score was performed as a symphony, it was rubbished by the Nazi-controlled press. Goebbels himself spoke derisively of Berg, grouping him with other composers whose experiments with atonality he dismissed as ‘the Jewish intellectual infection.’ Yikes! Berg died of sepsis in 1935 but the final sections of Lulu were reconstructed from his notes and it was performed in 1937 in Zürich.

One of the most interesting motifs of Lulu is the fact that she is constantly and conspicuously framed as the villain, first by a leering circus master who displays her like an animal in a nightmarish prologue and tells the audience she is the source of evil. From the connection with the story of Pandora to a portrait of Lulu as Eve, she is understood by the abusive men who prey upon her as the one responsible for their lust, as the origin of their sin. Yet already the audience is sceptical, already what is being done is working against what is being said (or, sung). At the beginning of the play, Lulu is about 15 and it is implied that she has been sexually abused by her father.

After a series of misadventures, Lulu has lost everyone except for Geschwitz, the woman who truly loves her. It is then that she meets Jack the Ripper, sometimes played as a new vision of Lulu’s former lover Dr Schön. He says he has no money to pay for her services but she agrees to have sex with him anyway. Jack murders her, then Geschwitz who has come running at the sound of her scream, and the play ends with the Countess declaring her love for Lulu with her dying breath as Jack the Ripper washes his hands and thinks himself lucky to have killed two women at once.

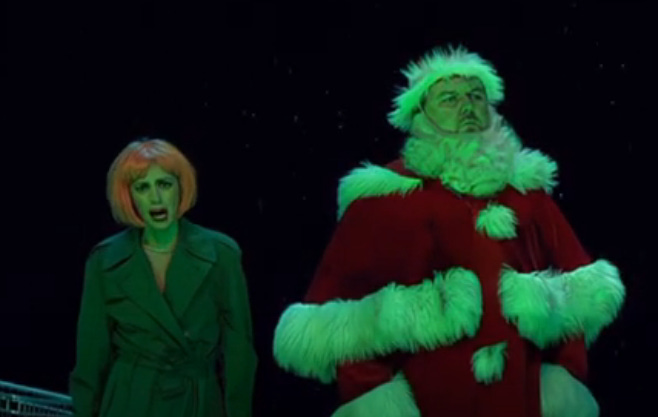

Different productions have done different things with ‘Jack,’ in fact the surreal tone established in the prologue seems to encourage bizarre non-literal choices throughout the opera. Strangely enough, Jack’s appearance often seems to borrow from depictions of unkillable murderers popularised in horror cinema. In one production, he is Father Christmas, a favourite disguise in the sub-genre of Christmas slashers.2

In another, he has the makeup of a killer clown.3

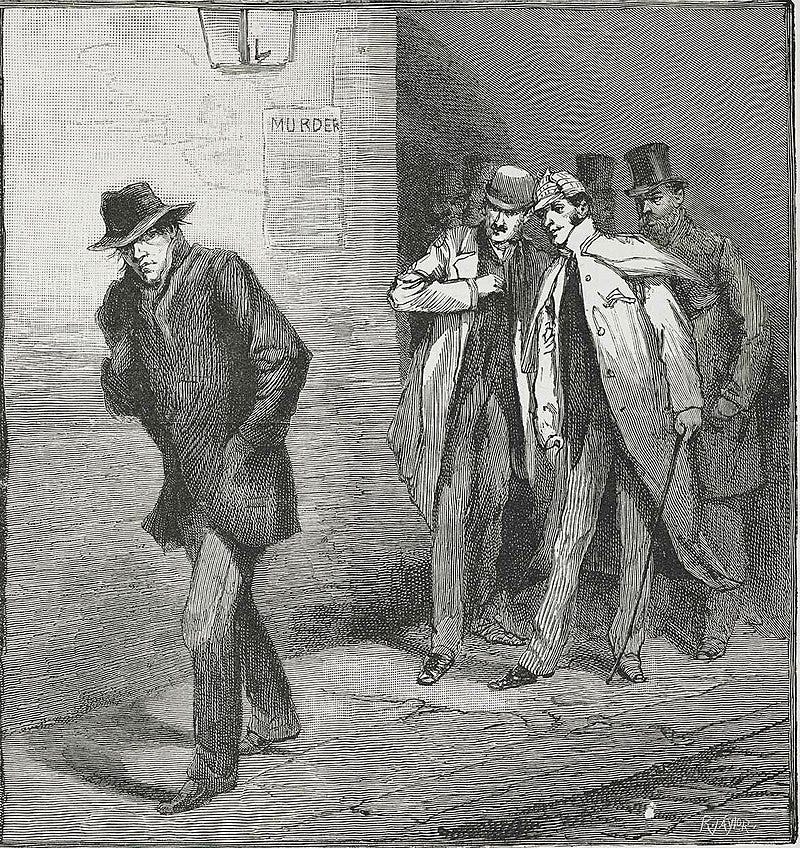

And so on. Very rarely is the opera staged in its original London setting, and it seems not to matter whether this is literally Jack the Ripper as we imagine him, rather that he is a manifestation of something evil that has lurked in all the male characters and is now given form. It is evil itself that Lulu encounters: a singing Michael Myers.

But Jack the Ripper was a real man and, more importantly, his victims were real women. How then, do you tell a true story about true murders using the operatic form?

Jack the Ripper: The Women of Whitechapel

In 2018, composer Iain Bell, a Londoner, and librettist Emma Jenkins brought to life the story of the five canonical victims. Jack the Ripper: The Women of Whitechapel was produced by the English National Opera and focussed on the lives of the five — Mary Ann ‘Polly’ Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly — as well as the story of the London working class. “It happened in our own city in our own London” says Susan Bullock who sang the part of ‘Liz.’

The score at times sounds like a horror film with slicing violins reminiscent of Psycho, and there are some grim visuals like the appearance of the bodies themselves on mortuary tables. Nevertheless, the opera aimed to focus on the living women. “These are women…whose identity is defined by their death, and I wanted to do something to explore their humanity, “ explained Bell. A decision was made early on that ‘Jack’ himself would never appear on stage.

(Incidentally, keeping Jack ‘offstage’ is tactic brilliantly used in Hallie Rubenhold’s biography The Five which explores the women’s lives without dwelling on the gory details of their deaths. It was recommended to me recently —thank you everyone on Bluesky! — and is the book to read if you’re interested in the topic.)

The Women of Whitechapel has a similar basic plot to Lulu. Just as Lulu is presented to us by the ringmaster as a wicked temptress, so the press decided that all five victims had been working as prostitutes (wrong) and therefore that they deserved their fate (wrong-er!) Like Lulu, their stories were far more complex, their personalities far more interesting, and their killer functionally indistinguishable from every other abuser who has stalked and murdered women. Jenkins, the librettist, commented: ‘we wanted to create this idea that it was society and London which almost consumes people, like a personification if you like of an energy a force that is unseen…and it’s that that consumes the women.’

Nevertheless, Jack’s shadow loomed over the production. The ENO insisted, against the wishes of the creative team, that the title be changed to add ‘Jack the Ripper’ to ‘The Women of Whitechapel.’ Understandable from a marketing perspective, but possibly also a sign that it’s not entirely possible to separate victims from murderers when it comes to real criminal cases.

In researching these works, I’ve uncovered a far more fascinating history than that half-remembered page in Kobbé's Opera had suggested. It turns out that opera, like horror, has experimented with different ways of depicting serial killers and their victims. It’s been heartening to see that, despite opera’s reputation for being stuffy, formal, and old-fashioned, storytellers working in this form have long been interested in giving victims of prejudice and violence their dignity and, both literally and metaphorically, a voice.

Horror moments are posted every Thursday and a wide variety of articles exploring the history of magic, theatre, storytelling, and more are published on Mondays.

Remember that you can pay to subscribe for extra benefits or buy me a coffee here to keep me writing. You can also like, share, comment, and recommend to help the substack grow. Thank you!

Cover image © Alastair Muir

Still from

Still from

I’m sure you know this but Metallica and Lou reed collaborated (yes) on a remake of Lulu.

It is… something

I actually kinda love how unhinged it is, which is not to say it is “good”

Thanks for this! An excellent read. I was aware of the film Pandora’s Box from the OMD single of the same name but this has tempted me to try to seek it out. The Five is also on my tbr list. I’m glad to hear it doesn’t disappoint.