When Good Stories Need Boring Bits

What the folk horror game 'The Excavation of Hob's Barrow' has in common with Jane Austen's 'Emma'

This week, my annual subscription is half price to celebrate reaching the latest milestone of 1,500 subscribers. You can also now buy me a coffee to keep me writing — or like, share, recommend, and comment to let me know that you’ve enjoyed Dr King’s Curiosities. Thank you so much for your support!

Please note: the first half of this article is spoiler free and I’ll put a clear spoiler warning halfway through.

Something Sinister in Bewley

It’s the year 18-something. Thomasina Batemen is walking in the footsteps of her father, an antiquarian with a passion for excavating ancient earthworks or ‘barrows.’ Ever since he suffered a mysterious accident which left him comatose, Thomasina has tried to continue his studies.

She is thrilled when she receives an invitation to the northern town of Bewley from one ‘Leonard Shoulder’ who tells her that they’ve got a particularly fascinating barrow waiting to be excavated.

Yet when Thomasina arrives at Bewley station she is greeted with a singularly inhospitable sight: a few grey stone houses standing on their own in the midst of the wide bleak landscape…and Mr Shoulder is nowhere to be found.

That night, in her temporary lodgings at the local inn, Thomasina has an extremely unsettling dream. She’s only just arrived and already there is dread in every shadow, but things are about to get much much worse.

Thus begins ‘The Excavation of Hob’s Barrow,’ a 2022 game by Shaun Aitcheson, John Inch and Laurie MH of Cloak and Dagger Games, published by Wadjet Eye Games.

To explain why I enjoyed it so much, I have to talk about a strange phenomenon found in a handful of particularly brilliant classic novels by the likes of Austen, Melville and Sterne. This is the art of being deliberately boring for narrative effect.

But first, let’s explain a key influence of the design and tone of Hob’s Barrow, namely:

Folk Horror

As those of you who are familiar with the genre will have already noticed, Hob’s Barrow is planted firmly in the folk horror tradition, where something sinister takes root in an isolated community and the very earth writhes with evil.

The game walks the line brilliantly between evoking all the cliches we expect and giving us new, sometimes incredibly nasty imagery that feels totally original. Cut scenes suddenly adopt a far more richly detailed animation style, often showing you precisely the squirming, disturbing details you don’t want to see up close.

There’s also a rich sense of character and humour throughout. The residents of Bewley all have their petty grievances and eccentricities. You grow fond and suspicious of them all in equal measure as the cold stony walls and rickety fences start to feel like home.

For the first couple of days you spend there, your life feels like a series of little errands punctuated by uncanny sights and nightmarish visions, but also by lovely memories of your father teaching you how to dig for artefacts before his horrible accident. You help an old lady honour her dead husband, arrange a rendezvous for an eloping couple, and fetch flowers and Bakewell tarts back and forth in slightly convoluted, occasionally maddening mundane tasks.

And then a glimmer of frustration sets in. There’s something slightly irritating about the game mechanics of Hob’s Barrow. Occasionally you feel as if you’re doing little more than clicking everything blindly just to see what works and completes the next leg of a quest. There are moments where it’s not at all intuitive and one step involving an apple that I genuinely don’t think I’d have ever guessed without cheating (thank you, Reddit.)

And that’s where you start to feel something which we might called ‘metatextual fatigue.’

Metatextual Fatigue

One of the cleverest storytelling tricks in all of English literature comes from Jane Austen’s novel Emma. In Chapter 1 of Volume II, Emma and Harriet call in on Mrs and Miss Bates. Emma doesn’t really want to be there and Miss Bates has a habit of talking and talking and talking…

“Oh! here it is. I was sure it could not be far off; but I had put my huswife upon it, you see, without being aware, and so it was quite hid, but I had it in my hand so very lately that I was almost sure it must be on the table. I was reading it to Mrs. Cole, and since she went away, I was reading it again to my mother, for it is such a pleasure to her—a letter from Jane—that she can never hear it often enough; so I knew it could not be far off, and here it is, only just under my huswife—and since you are so kind as to wish to hear what she says;—but, first of all, I really must, in justice to Jane, apologise for her writing so short a letter—only two pages you see—hardly two—and in general she fills the whole paper and crosses half. My mother often wonders that I can make it out so well. She often says, when the letter is first opened, ‘Well, Hetty, now I think you will be put to it to make out all that checker-work’—don’t you, ma’am?—And then I tell her, I am sure she would contrive to make it out herself, if she had nobody to do it for her—every word of it—I am sure she would pore over it till she had made out every word. And, indeed, though my mother’s eyes are not so good as they were, she can see amazingly well still, thank God! with the help of spectacles. It is such a blessing! My mother’s are really very good indeed. Jane often says, when she is here, ‘I am sure, grandmama, you must have had very strong eyes to see as you do—and so much fine work as you have done too!—I only wish my eyes may last me as well...’”

…and talking and talking and talking…

…“So obliging of you! No, we should not have heard, if it had not been for this particular circumstance, of her being to come here so soon. My mother is so delighted!—for she is to be three months with us at least. Three months, she says so, positively, as I am going to have the pleasure of reading to you. The case is, you see, that the Campbells are going to Ireland. Mrs. Dixon has persuaded her father and mother to come over and see her directly. They had not intended to go over till the summer, but she is so impatient to see them again—for till she married, last October, she was never away from them so much as a week, which must make it very strange to be in different kingdoms, I was going to say, but however different countries, and so she wrote a very urgent letter to her mother—or her father, I declare I do not know which it was, but we shall see presently in Jane’s letter—wrote in Mr. Dixon’s name as well as her own, to press their coming over directly, and they would give them the meeting in Dublin, and take them back to their country seat, Baly-craig, a beautiful place, I fancy. Jane has heard a great deal of its beauty; from Mr. Dixon, I mean—I do not know that she ever heard about it from any body else; but it was very natural, you know, that he should like to speak of his own place while he was paying his addresses—and as Jane used to be very often walking out with them—for Colonel and Mrs. Campbell were very particular about their daughter’s not walking out often with only Mr. Dixon, for which I do not at all blame them; of course she heard every thing he might be telling Miss Campbell about his own home in Ireland; and I think she wrote us word that he had shewn them some drawings of the place, views that he had taken himself. He is a most amiable, charming young man, I believe. Jane was quite longing to go to Ireland, from his account of things…”

…and talking and talking and talking…

“And so she is to come to us next Friday or Saturday, and the Campbells leave town in their way to Holyhead the Monday following—as you will find from Jane’s letter. So sudden!—You may guess, dear Miss Woodhouse, what a flurry it has thrown me in! If it was not for the drawback of her illness—but I am afraid we must expect to see her grown thin, and looking very poorly. I must tell you what an unlucky thing happened to me, as to that. I always make a point of reading Jane’s letters through to myself first, before I read them aloud to my mother, you know, for fear of there being any thing in them to distress her. Jane desired me to do it, so I always do: and so I began to-day with my usual caution; but no sooner did I come to the mention of her being unwell, than I burst out, quite frightened, with ‘Bless me! poor Jane is ill!’—which my mother, being on the watch, heard distinctly, and was sadly alarmed at. However, when I read on, I found it was not near so bad as I had fancied at first; and I make so light of it now to her, that she does not think much about it. But I cannot imagine how I could be so off my guard. If Jane does not get well soon, we will call in Mr. Perry. The expense shall not be thought of; and though he is so liberal, and so fond of Jane that I dare say he would not mean to charge any thing for attendance, we could not suffer it to be so, you know. He has a wife and family to maintain, and is not to be giving away his time. Well, now I have just given you a hint of what Jane writes about, we will turn to her letter, and I am sure she tells her own story a great deal better than I can tell it for her.”

You get the picture. Miss Bates is well-meaning but once she gets started she can’t seem to stop herself and goes on for huge paragraphs of dialogue at a time. For some reason, Austen is making us read every single word. Pages go by, you perhaps put down the novel to go and make yourself a cup of tea, or check your phone…

Suddenly, Emma saves us:

“I am afraid we must be running away,” said Emma, glancing at Harriet, and beginning to rise—“My father will be expecting us. I had no intention, I thought I had no power of staying more than five minutes, when I first entered the house. I merely called, because I would not pass the door without inquiring after Mrs. Bates; but I have been so pleasantly detained! Now, however, we must wish you and Mrs. Bates good morning.”

Thank god, we think. That was quite enough of that.

So Austen has pulled off a trick which a lesser author would never have dared to attempt. Instead of writing words to the effect of ‘Miss Bates droned on and on for a while’ she gives us the conversation virtually verbatim so that we have to sit through it just as Emma does. Emma saves us as well as herself by that quick exit, and we have felt what it’s like to be in the eye of Miss Bates’ conversational skills, which will pay off much later in the novel in one of the most important moments.

We are now in Chapter 7 of Volume III. Emma has gone out for the day with a group of friends which includes Miss Bates and a young man called Frank Churchill. Frank sets up the rules of a game to entertain Emma: everyone else must either say one very clever thing, two moderately clever things, or three dull things and she will ‘laugh heartily’ at them all.’

Miss Bates, who is not as lacking in self-awareness as perhaps we thought, makes quite a good self-deprecating joke:

“Oh! very well,” exclaimed Miss Bates, “then I need not be uneasy. ‘Three things very dull indeed.’ That will just do for me, you know. I shall be sure to say three dull things as soon as ever I open my mouth, shan’t I? (looking round with the most good-humoured dependence on every body’s assent)—Do not you all think I shall?”

And in reply?

Emma could not resist.

“Ah! ma’am, but there may be a difficulty. Pardon me—but you will be limited as to number—only three at once.”

It’s such a small but devastating moment. Poor Miss Bates is mortified. Is this how everyone secretly feels? Has she really been a horrid bore to them all along, most of all to Emma who is so ‘handsome, clever, and rich,’ someone whose opinion she respects? She goes quiet. There are none of those conspicuously massive paragraphs now.

Later that day Emma’s friend, Mr Knightley, corners her and tells her off. The famous line is “It was badly done, indeed!” and it’s at this moment that Emma really feels that she has gone too far, that she has punched down on someone who lacks her advantages in life and has done nothing wrong except commit the terrible crime of being a bit dull.

Like a guilty accomplice drooping our head, the reader is totally implicated in this lesson, something that wouldn’t have happened if Austen hadn’t made us sit through those earlier conversations, hadn’t made us feel Emma’s boredom and hadn’t encouraged us to delight with her in that moment of revenge.

So that’s what I mean by ‘metatextual fatigue,’ a boredom or frustration not merely described in the course of the story but inflicted on the reader for good reason. Other classics that make use of this device are Tristram Shandy (a comic novel written from the perspective of the last person in the world who should be writing a novel) and Moby Dick (where somehow the lengthy digressions on whale taxonomy feel as vital as the action sequences.) Let me know if you can think of others.

In Hob’s Barrow, you need to push through the frustrations and the mundane minutiae of the plot, exacerbated by the slightly awkward game mechanics. It’s important that all of that slows you down because it is precisely this pacing that makes the place where the game ends up feel all the more upsetting.

SPOILERS FOR HOB’S BARROW FROM NOW ON!

The Final Day

Hob’s Barrow is a game that genuinely stayed with me after I had played it. For all that the middle section could be frustrating, it was building up a sense of familiarity with Bewley and a fondness for its residents which would make the feeling of betrayal all the sharper when I realised that I had completely misjudged where the story was leading me.

I suppose I thought, on some level, that the game would bring me resolution. That Thomasina would discover what happened to her father in the accident and be able to cure him or (in a darker ending) put him out of his misery.

The solution felt like a sick joke, with a fatalistic sense that all the while I had been walking blindly towards my doom.

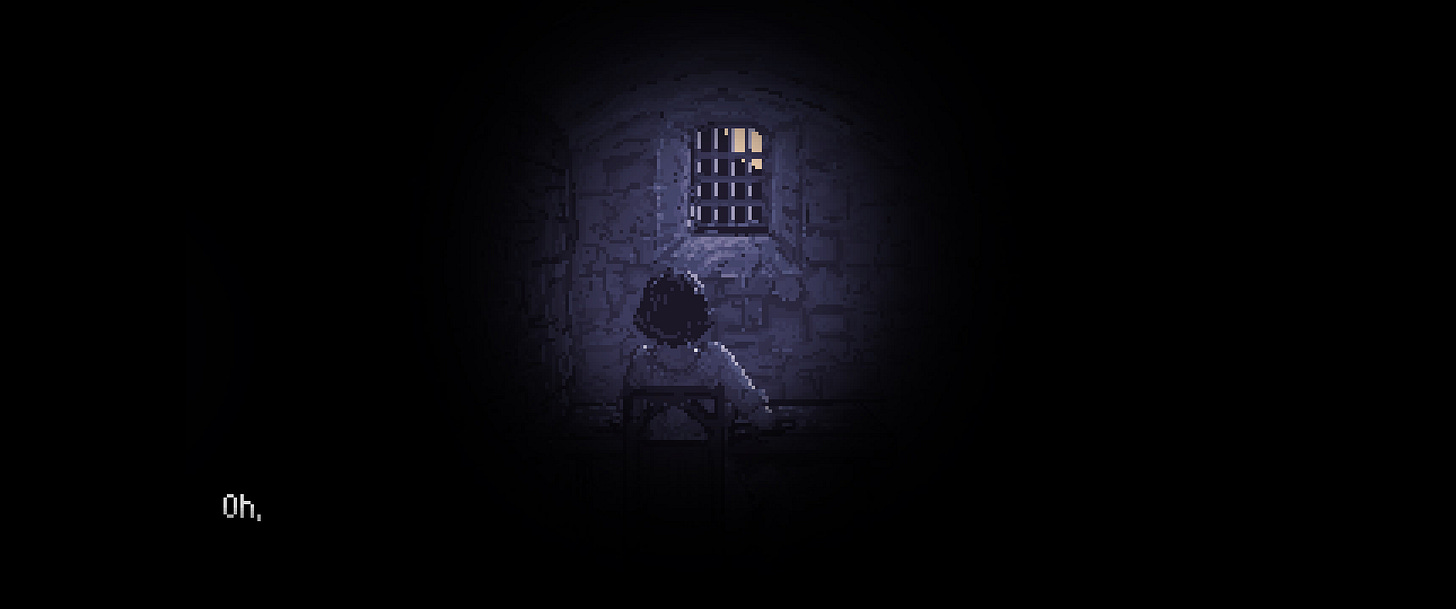

On the final day, Thomasina enters the barrow and everything that gave us comfort or companionship is gone. She is alone in the sickly purple corridors of a place that feels vile. I thought I was heading in to seal up a demon in the earth forever, and I felt incredibly stupid looking back for not noticing that every foreboding detail was telling me the truth: I was being used to reverse the binding that had kept it in the ground. I had been set up by Leonard Shoulder and, it turns out, half of Bewley, who knew all along what I was there to do.

The sickest twist is what happens to her relationship with her father. As she nears the horrid spirit (which we never fully see), we relive the visions that had given us flashbacks of happier days or wistful memories of her father lying peacefully in bed. Now they are distorted, her mind is rotting and the images are turning to worms. The nastiest shock of the whole game is a horrible twist on a moment when Thomasina pulls back the bedsheets that he says are making him too hot…

We then find out what happened after we unleashed the thing in Hob’s Barrow. How Thomasina’s mind was totally corrupted and she headed home to end her father’s torment — by smashing his head in with an antique vase. Her bitter narration to her mother has, we find out, all along been the letters she has been sending from prison trying to make sense of this episode of insanity.

It feels by the end as if everything about the game has betrayed you, that you have genuinely done something awful, that you’ve been stupid and gullible – a feeling I’ve never quite had with any other game. Those central sections in Bewley are so important for creating the circumstances of betrayal.

Folk horror at its best isn’t really about creepy hares and ravens, it’s about the horror of the ‘folk,’ a community gone bad. Hob’s Barrow makes you part of a community, then reveals that you have never really been accepted. It builds a tapestry of relationships, then shows you that only half were ever sincere. You look back on all the little good deeds you did for various people and realise that some were out to get you all along. It’s the ending of The Wicker Man — and you’re the fool.

When we’re taught how to tell stories at school, we’re told sensible foundational rules about not being boring, about telling the tale succinctly and efficiently, about being careful not to lose your reader. Oddly enough, it seems to be games that are beginning to exploit reader expectations by learning a lesson the very greatest novelists have taught us: that breaking the rules to torment a reader sometimes makes for the best stories of all.

Subscribe for more articles on a range of fascinating subjects. I publish my ‘horror moments’ on Thursdays, and other curious articles like this on Mondays.

You're right, that scene in Emma certainly did showcase how tedious people who love the sound of their own voice are. So tedious,in fact, that I put it down and have no intentions of going back to it. 😅

It's on my steam wishlist 😅