A few subscribers have been asking me what my thoughts are on the recent Robert Eggers Nosferatu (2024) which was released in the UK on New Year’s Day 2025. My PhD thesis was all about depictions of magicians, particularly those who modelled their occult experiments on apocryphal stories about King Solomon. Eggers has quite conspicuously included Solomonic magic in the film, so I thought it would be fun to explore what that’s doing and how it makes this version of the vampire story subtly different from its predecessors.

Occultism in the 1922 Film

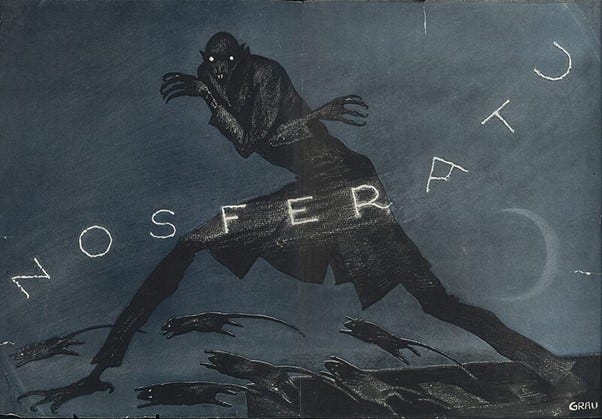

The original Nosferatu was a silent German film from 1922, directed by Friedrich Murnau and produced by Albin Grau. It’s often described as ‘Dracula with the serial numbers filed off’ and the fact that it was, essentially, an unauthorised adaptation of the 1897 novel sparked a copyright war with Bram Stoker’s widow. Some of the changes may seem, superficially, to be attempts to cover these tracks: Count Dracula becomes Count Orlok, we get rats instead of bats, and the vampire travels not to London but to Wisborg: this is German Romanticism not Victorian melodrama.

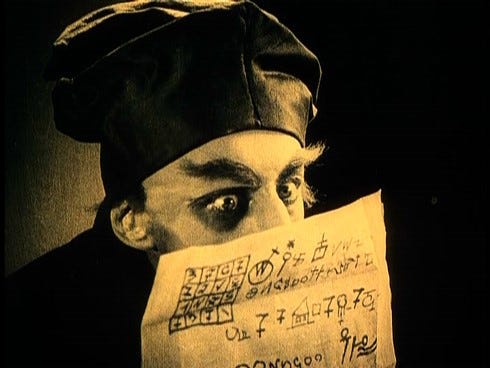

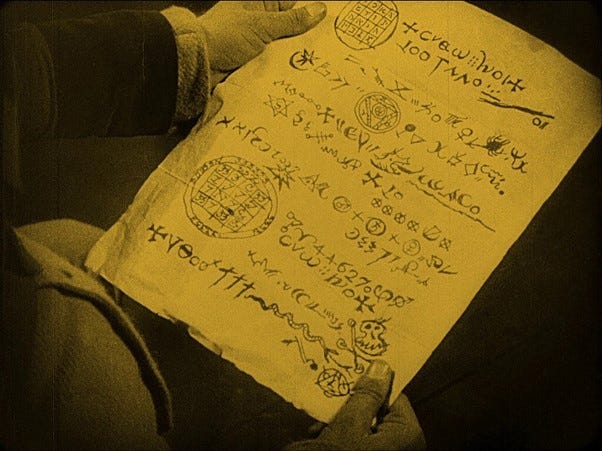

In recent interviews, Eggers has insisted that the changes the original Nosferatu made to Dracula are far more thoughtful than mere copyright dodges and some good example of this are found in the additions made by producer Albin Grau. A member of the German magical order ‘Fraternitas Saturni,’ Grau added elements of a particular kind of occult tradition to the film. You can see some of this influence in details like the symbols on the letters Orlok writes and the strange contract he draws up for the young hero to sign. These are hermetic and alchemical codes that belong to a specific kind of learned magic associated with men and with scholars: not witches in the woods, but conjurors in their studies.

Significantly, Orlok himself is a demonic presence in the 1922 film. He is said to have been a creation of the archdemon Belial who is mentioned in the Bible and is also supposedly an embodiment of plague and disease. Some of those changes from Dracula are thus more thematically appropriate: rats are better than bats not only because they make this version of the story visual distinct, but because the sight of them flooding off the ship into Wisborg brings to mind the Black Death. Here we get the ‘Great Death’ of Wisborg, a supernatural disease which threatens the whole town.

On the other hand, there’s also a suggestion that Orlok was once human, a sort of magician-gone-bad. He communicates with his accomplice Knock (the counterpart of Renfield in the Dracula story) using what Grau’s occultist friends would have recognised as the magical Enochian language which had been developed by Elizabethan magician John Dee and his scryer assistant Edward Kelley in their attempts to contact angels. It’s basically Wingdings c.1600. Maybe that’s what Windings was for all along.

This is great fun for me because it means there is a direct link between these films and a specific kind of magic that was being debated in my period of study and was depicted and parodied on the early modern stage. One of John Dee’s grimoires ended up in the library of Ben Jonson, a great playwright of the period, who poked fun at these systems of belief in his play The Alchemist (1610) which mentions Kelley by name.

The question all this raises from a storytelling point of view, is whether or not we are meant to view Orlok as an elemental force of evil, a human being who experimented with magic and was corrupted, or a bit of both. The 1922 film never quite resolves these tensions and it doesn’t really need to. That original Nosferatu is a wonderful piece of horror cinema which still holds up a hundred years later, stylish and sinister with a phenomenal central performance by the appropriately named Max Schreck and ground-breaking use of menacing architecture and looming shadows.

Solomonic Exceptionalism

Before I turn to Eggers’ version, which comes to a slightly clearer conclusion about what Orlok is, it’s important to talk about Solomon’s role in all of these discussions. My PhD looked at the way that theatre in the late sixteenth/early seventeenth century helped to codify ideas about different forms of magic and dangerous knowledge seeking. I studied the development of belief in a particular kind of special exemption from general prohibitions against experiments with the supernatural occult.

To put it very simply: in the Christian tradition, Solomon was the wisest king who ever lived. The Bible mentions that he wrote down some of his wisdom, but doesn’t clarify exactly what that means and whether those books still exist in the world somewhere. This gave rise to a non-biblical or apocryphal tradition where particular tomes of learning would be attributed to Solomon himself.

This appealed to practitioners of the magical occult. If you could attribute your grimoire of magic to Solomon, it might legitimise your work and help you dodge accusations from the church that what you were doing was dangerous or sinful. After all, if Solomon had designed and performed these experiments, they couldn’t be inherently evil, could they? Solomon was even capable, it, was said, of conjuring and commanding demons without becoming corrupted by them, a bit like how a judicious monarch might imprison and put to work the convicts that might otherwise cause trouble.

Men – and it very much was mostly men – who used the figure of Solomon in this way were reaching for something which I have called ‘Solomonic exceptionalism: ‘I am like Solomon, therefore I’m above criticism or, if you prefer, ‘I am like Solomon, so I’m in charge of the demon, not the other way around’. This assertion is particularly important in the early modern period because you could be executed for using witchcraft/black magic and many believed that you risked your soul by seeking out powers and knowledge beyond what God had revealed in the natural world. The story of Doctor Faustus is the archetypal study in what happens when a man’s belief in his own Solomonic exceptionalism leads him into hubristic experiments with magic that, um…don’t go well.

Eggers’ Solomonic Vampire

I’m going to go into Solomonic exceptionalism in a bit more detail in some future articles so I’ll stop for now, but keeping this context in mind is important for understanding some of Eggers’ choices in his new film. Eggers has added lots of details to the characterisation of Count Orlok that make it far clearer than in the original that he was once, in some form, human. Yes he has become something other than human, as he tells us in his deep Transylvanian accent: “I am an appetite” and yes he represents plague, death, lust and all the rest, but we know far more explicitly this time that he was once a real Romanian nobleman.

Gone are the rabbity teeth and the goblin ears of Max Shreck’s costume and here instead is the long thick moustache of an authentic medieval nobleman from Eastern Europe. We are told that he was once a magician and we see more tell-tale signs of Solomonic magic which imply that Orlok has ended up like this because he gave himself over to darkness during his magical attempts to gain power.

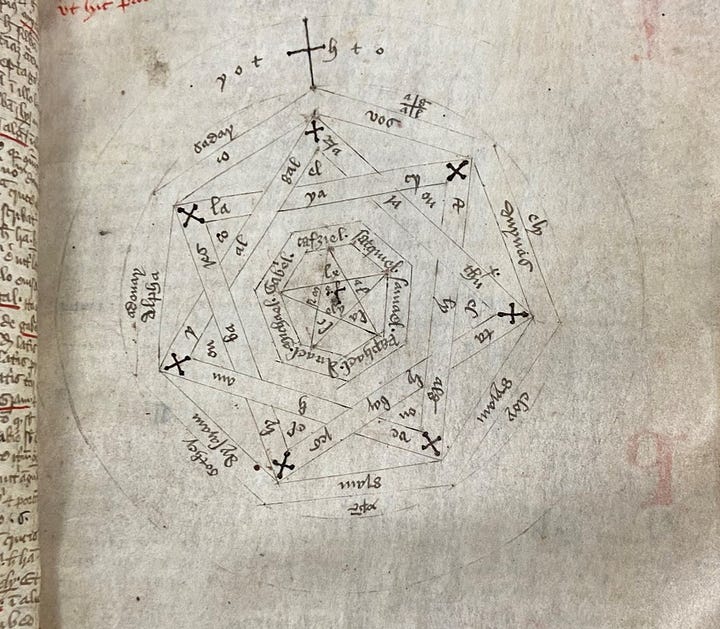

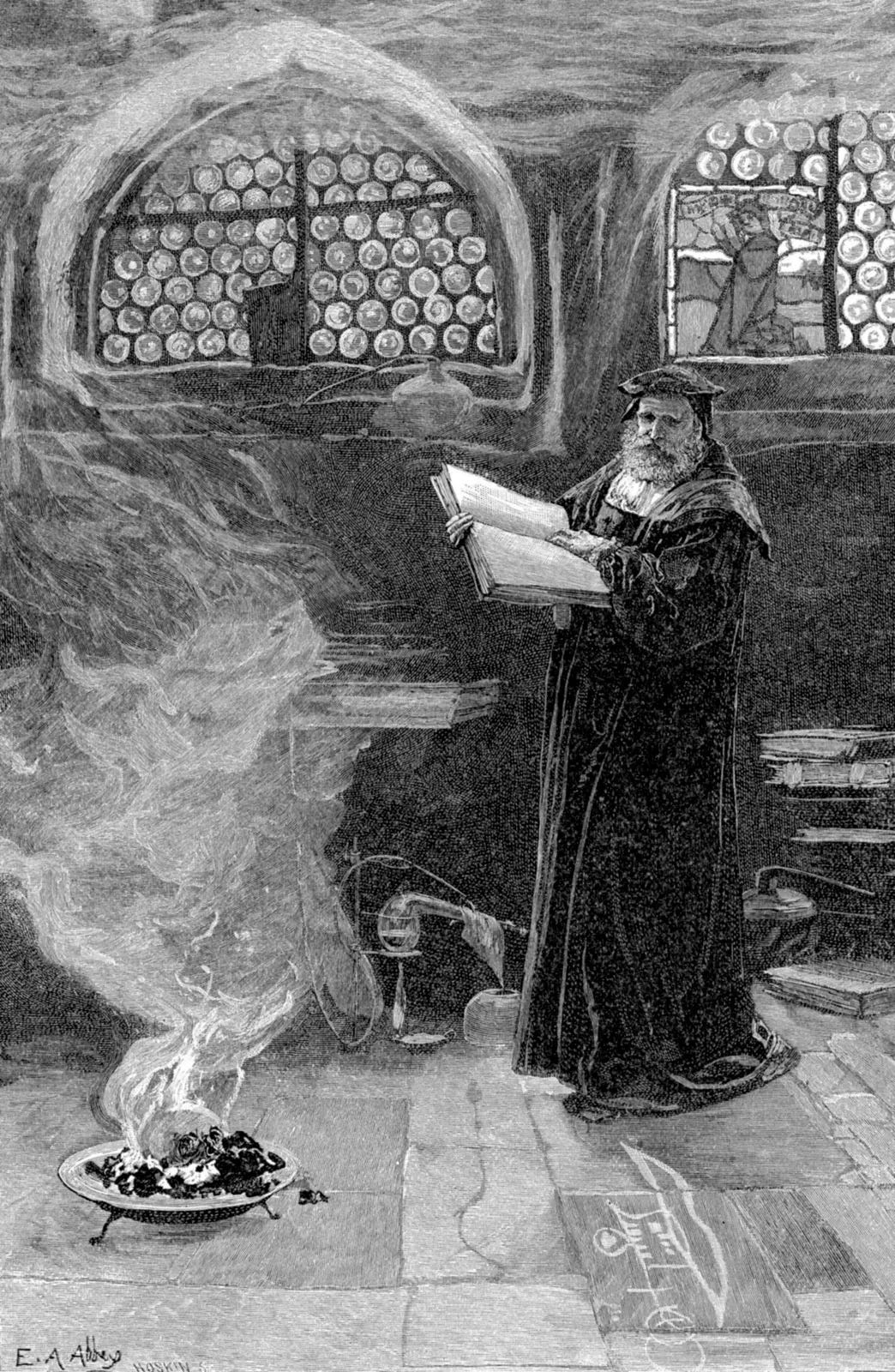

You can see a quintessentially Solomonic magical motif in this shot from the trailer, showing an elaborate grimoire illustration extremely similar to the seals in real books of magic attributed to Solomon:

That second picture comes from the same grimoire I mentioned earlier, the one that belonged to the magician John Dee and was owned by the playwright Ben Jonson. It was listed in Jonson’s library as ‘Salomonis opus sacrum ab Honorio ordinatum, tractatus de arte magica,’ (‘Salomon’s sacred work, ordered by Honorius, treatise of the magical art.’)

I couldn’t get a shot online but you see one of these motifs on the outside of Orlok’s coffin and on various other details throughout the film. These sorts of seals come from legends about Solomon being able to use his symbols (the knot or star) to command demons to do what he wanted. Sometimes a magician would draw them on the floor, on objects or signet rings to essentially borrow this Solomonic authority.

It's appropriate that the Nosferatu tradition, first through Grau and now even more overtly in Eggers, should have played up the notion of a vampire being a Solomonic magician because this is actually true to the original Romanian folklore. The ‘Solomonari’ were a group of fabled magicians who rode dragons and controlled the weather. They were taught magic – again there is an emphasis here on scholarship and masculine upper class authority – in a secret school, the Scholomance, which was hidden in the mountains. The catch was that the scholars themselves were tithed: one out of each cohort of ten magicians was taken by the Devil. The nineteenth century folklorist Emily Gerard had brought knowledge of these myths to Britain in her 1885 Transylvanian Superstitions and Land Beyond the Forest (1888).

Stoker uses all this context for Dracula but is only fleetingly interested in the concept of the Solomonari and their implications for his vampire. Perhaps Stoker was less personally concerned with the promises and pitfalls of learned magic than Albin Grau. Playing up this aspect of the source material is part of what distinguishes a Nosferatu story from a Dracula story, and all of these Solomonic dimensions of Orlok himself have been reactivated and enhanced in the 2024 film.

Other Solomons in the Story

Another element that Eggers plays up is the role of other men who are, in one way or another, on the same path of occult learning as his version of the vampire. There is Knock, whom we see naked with his grimoire in the middle of a Solomonic circle, conjuring under the instruction of Orlok. He, played with glee by Simon McBurney, is a squalid sycophant, very much a cautionary figure. He ends up a murderous geek – I word which I am using in its carnival sense to mean someone who bites the head off living things – controlled by and certainly not controlling the evil forces he’s unleashed. There’s an interesting moment later in the film when he laments that the vampire promised him he could be ‘king of the rats’ but has in fact abandoned him: here is the hubris and the fall that we find in the Faustus myth and other sceptical responses to the idea of Solomonic exceptionalism.

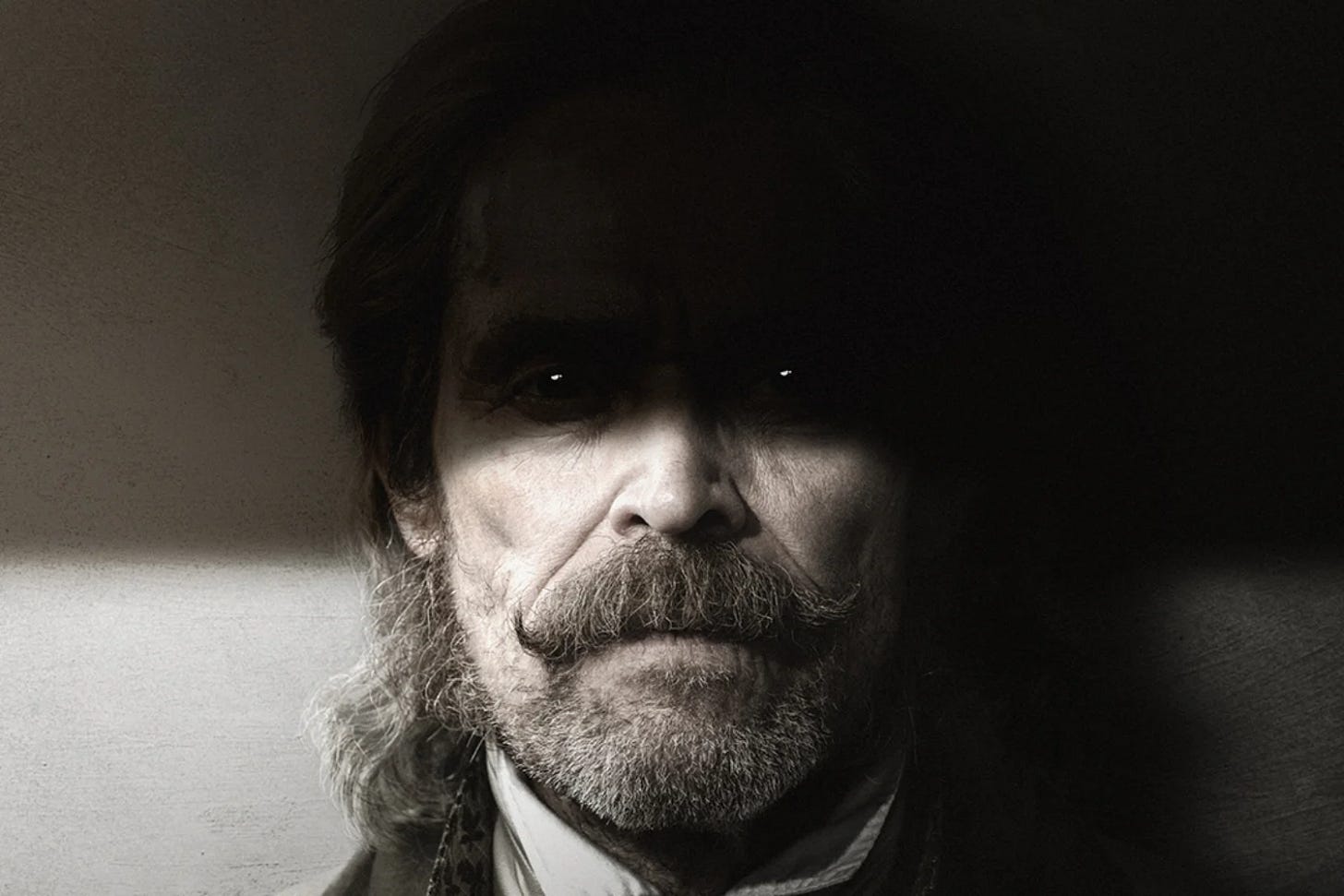

More complex is Willem Dafoe’s character, Albin Eberhart Von Franz, who is sort of our Van Helsing here but much more importantly takes on the role of a successfully Solomonic occultist. When their scientific approaches have failed, our main characters go to seek him out in the kind of book-stuffed garret that is supposed to indicate his eccentric isolation and economic hardship but to me looks ideal and extremely cosy. He’s been kicked out of the establishment for his obsession with the esoteric arts, with alchemy and astrology, with Paracelsus and Agrippa (two Solomonic figures from the history of magic).

I’ve heard some criticism that his character isn’t really necessary since Ellen, the woman whose strange connection to the vampire has drawn him into Germany, seems to intuitively understand the sacrifice she has to make to end the plague. Yet, if we see the plot in terms of different kinds of men attempting Solomonic exceptionalism, his significance becomes a little clearer.

We have a total failure, Knock, driven mad and made pathetic by his petty lusts and greed, we have Orlok, grand and noble, warped into a far more powerful evil entity by his dangerous occult experiments, and we have Albin, perhaps the truest Solomon of them all, stepping in with his wisdom and good judgement to help save the day. He is the kind of figure that his namesake Albin Grau and his fellow occultists aspired to be: a man with enough knowledge and self-control to navigate these strange frontiers without succumbing to corrupting ‘appetites.’

On the other hand, we don’t know the end of his story. We don’t know what happened after the events of the film. Perhaps the reason his role feels less significant, is because it’s only just begun. A subtextual menace at the end of Eggers’ version, if you know your magical history, is that Albin Von Franz is on the same spectrum of Solomonic learning as the character who has been the central menace of the tale. In him are the same ingredients – masculinity, education, intelligence, ambition – that can combine in an unholy alchemy to turn the base matter of a mortal man into that mighty and undying spectre, that walking pestilence, that Nosferatu: the vampire.

Subscribe for more articles on a range of fascinating subjects relating to horror, magic, theatre, special effects and more. I publish my ‘horror moments’ on Thursdays, and miscellaneous articles like this on Mondays.

It sounds like you got a lot more out of the latest Nosferatu than I did! (Though I was amused by the "Van Helsing" character dissing science but then showing that his best weapon against the vampire was kerosene -- not actually available to us ordinary mortals till years after the events of the story.) But... surely, given the Herzog version, here was the perfect opportunity for a segue to Kate Bush's work by way of Florian Fricke and Popol Vuh?

'the kind of book-stuffed garret that is supposed to indicate his eccentric isolation and economic hardship but to me looks ideal and extremely cosy' - yes! Give me a book-stuffed garret any day.