Eye-popping Effects – The blinding of Gloucester in King Lear and the history of eye gouging on stage and screen.

Horror Moments, Shakespeare Edition

[Spoilers: King Lear (1605), Lear (1971), Blasted (1995)]

‘Horror Moments’ is a series examining horror-inflected scenes and themes in unexpected places. The ‘moments’ are published weekly on Thursday mornings, and I share a range of articles on the history of magic, theatre, storytelling, and more on Monday afternoons – don’t forget to subscribe!

The blinding scene in King Lear (c. 1605) is one of the most brutal, cruel, and borderline insane episodes in all of the works of Shakespeare.

We are in Act 3 scene vii, and everything is very much in crisis. The old, unstable King Lear has been banished from his own court by two of his daughters: Regan and Goneril. The Earl of Gloucester, faithful to Lear, has deliberately hidden the fact that an army is on its way to save the king — but someone dobs him in and he is arrested.

Gloucester is now at the mercy of Regan, and her husband the Duke of Cornwall. They demand to know why he has sent the king to Dover. The real reason is because that’s where the rescuing army will land, but Gloucester defiantly says:

GLOUCESTER

Because I would not see thy cruel nails

Pluck out his poor old eyes…

Brave and foolish, his words do nothing to assuage his captors’ fury:

CORNWALL

See't shalt thou never. Fellows, hold the chair.

Upon these eyes of thine I'll set my foot.GLOUCESTER

He that will think to live till he be old,

Give me some help! O cruel! O you gods!

One of Gloucester’s eyes is being gouged out as he screams these last words. This was the point in the production I saw as a teenager when a ten-year-old had to be taken out from The Courtyard Theatre in floods of tears.

Shakespearean-era plays make sparing use of stage directions. They use what’s called ‘implied stage directions,’ where the actors can figure out what they need to do based on the lines themselves. This means that there is no information about exactly how the blinding happens – although Cornwall’s threat implies that he stomps on the eyeball after it is removed.

We don’t know exactly what early modern plays used for this effect, but an animal eye seems likely. I went to a Royal Shakespeare Company workshop on special effects once where they demonstrated how a lychee had been used in one production, smeared on the glass of a transparent box in which the mutilation scene took place — not a fruit that was readily available in Shakespeare’s day.

We know that this is the line when the torture begins because the next thing anyone says is the appalling instruction from Regan:

REGAN

One side will mock another; the other too.

A horrified servant tries to step in at this point, but he is killed. Extracting the second eye Cornwall gloats:

CORNWALL

…Out, vile jelly!

Where is thy lustre now?

So Gloucester is blinded. To add insult to injury, Regan’s final command to the trembling servants who remain is simply:

REGAN

Go thrust him out at gates, and let him smell

His way to Dover.

What a horrible scene! So horrible, in fact, that it was for a long time simply not staged. In Victorian theatre, the blinding became literally ‘obscene’ a word that comes from the Greek ‘ob skené’ or ‘off-stage.’ The most famous blinding in Greek drama happens offstage when the protagonist of Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex reappears covered in blood having put out his own eyes in his grief.

Early twentieth century productions gradually began to reinstate the blinding scene but usually had Gloucester’s back to the audience. It was Peter Brook’s staging in 1962 that turned him around again, his face on full display.

We’re getting more Jacobean in our sensibilities, possibly in part because of the rise and popularity of horror cinema, and if you go to the theatre today you can expect to see the eye-gouging in gory detail. Brook’s Cornwall had used the spur of one of his boots to perform the mutilation, and directors seem to be competing to fill in the gap left by the implied stage direction with the most memorable blinding apparatus they can imagine.

Jumping back to Shakespeare’s original audience we must remember that real gore was never far removed from the performances of plays. There’s a great book on this, Stage, Stake, and Scaffold by Andreas Höfele which explores the close proximity between the theatre and the sites of blood sports and public execution. Crossing London Bridge to go to see a play in Southwark, people would have passed the real heads of traitors on spikes above the gates, their eyes plucked out by birds.

The theatres themselves doubled up as sites of bear baiting and cock fighting (hence theatre names like ‘The Bear Garden’ and ‘The Cockpit’) where poor beasts chained to stakes were forced to fight for their lives. A handy source, perhaps, of eyeballs for actors to use in Gloucester’s blinding.

Gore had a traditional purpose in religious storytelling too. Before the Reformation, images of mutilated saints abounded. St Lucy is often depicted with her eyes on a plate like The Pale Man from Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), though hers often look decidedly fed-up.

A while ago a puppet theatre I sometimes write for commissioned a play from me about the history of St Albans which was performed in the cathedral, so I learned that during Alban’s martyrdom the eyes of his executioner were supposed to have sprung from his head.

I couldn’t include this in my script (tricky to do with marionettes) but brilliantly the two eyes appear as separate characters in the annual procession that retells the story of his life so two local children get to play eyeballs for a day.

Speaking of puppets, in the last hundred years the place to go to see a convincing stage blinding was Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol or ‘The Theatre of the Great Puppet’ which shocked Parisians from its opening in 1897 to its closure in 1962 – the same year that Peter Brook’s King Lear turned Gloucester around again to face the audience.

Not actually a puppet theatre (its name is metaphorical), the Grand-Guignol was an important bridge between the gore of the Elizabethan and Jacobean stage and modern productions that depict violence in graphic detail. It is also often cited as a powerful influence on the horror genre, particularly splatter and slasher films.

Typical plots revolved around melodramas and true-crime style stories of mutilation and murder, sometimes with a supernatural element. If you want to know how to make it look like something horrible is happening to someone, the Grand-Guignol will have figured it out.

Try, for example, ‘Eye-gouging with surgical scissors by two insane women, jealous of a beautiful fellow patient who is about to be released’ from Crime in a Madhouse.

If you like your mutilations to have meaning behind them, you’re better off with the bleak pioneering work of late-twentieth century playwrights like Sarah Kane and Edward Bond. Kane’s Blasted (1995), an important if difficult watch, draws on King Lear and shows a character’s eyes being sucked out on stage. I won’t do the play the injustice of a pithy interpretation, suffice it to say that Kane takes violence seriously.

She said:

“Acts of violence simply happen in life, they don’t have a dramatic build-up, and they are horrible. That’s how it is in the play. Critics would prefer it if there was something artificial or glamorous about violence.”

Kane was also building on Edward Bond’s Lear (1971), which adds a deafening-by-knitting-needle and an onstage autopsy to his loose adaptation of Shakespeare’s plot. The Methuen student edition of the play uses the image of a blinded man as its front cover, though here it is Lear himself who is the victim, his eyes sucked out by a machine a la Saw X (2023).

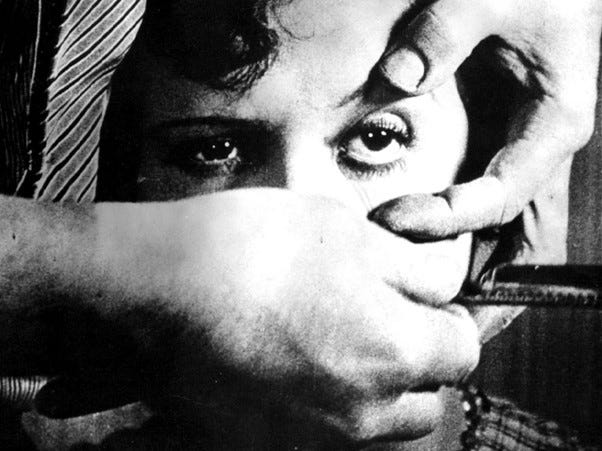

When it comes to the cinema, eyes are most memorably removed using practical effects not so very different from the kind you get onstage. The ground-breaking surrealist film Un Chien Andalou (1929), co-written by Salvador Dali and deliberately impossible to make sense of, is famous for a shot in which a woman sits passively as her eye is slit open by a razorblade.

The effect is disgustingly realistic because it was a real dead calf’s eye, which brings us all the way back to the probable use of animal eyes on the early modern stage.

From Un Chien Andalou to Hostel (2005), blindings on screen provide memorable (if sometimes anatomically dubious) moments. At times they invite reflection and analysis: is the loss of sight symbolic? Does the violence speak to broader cruelties and injustices? Is a character transformed through mutilation? At times the motivation seems to have simply been ‘what’s the most horrible thing we can do to a person and how can we make it look cool?’

So which one is Shakespeare? Were the Victorians right to hide the horror of Gloucester’s torture? Do we need to see it staged so explicitly?

One of the things that often tips the balance for me between finding a gory scene compelling or gratuitous is what happens afterwards. Shakespeare, Bond, and Kane make an audience live with the consequences of the mutilations they depict. We are not allowed to get a cheap thrill from a horrible moment and then toss the victim aside. Gloucester survives and we live with his despair and the despair of those who love him. This is also true of an even more brutalised character from another Shakespearean tragedy— I’ll be talking about that scene soon.

Until then, happy nightmares everyone, and as a postscript here's a delightfully disgusting video explaining how to get the right kind of spray of watery blood when making fake eyeballs for the stage for all your amateur productions of King Lear, described with straight faces as a recipe that is ‘safe for the eyes.’

Horror moments are posted every Thursday and a wide variety of articles exploring the history of magic, theatre, storytelling, and more are published on Monday afternoons.

I'm fight directing for a production of Macbeth at the moment.

In my experience (and this is true for this production), I'm not a core part of the production team. I'm an outside specialist who does a specific job for a limited part of the rehearsal timeline. I choreograph the show's fights, I train actors to perform them, and I send them back to the director.

I do my work in service of the themes of the show as they have been communicated to me by the director, but I don't witness my work in the context of the broader show while it's still in-progress. You talk about how much violence is justified by its aftermath, but as the person creating the violence, I have to trust that other artists are going to justify my work. It's super scary.

We used grapes in a local pro production a few years back—Regan was the one who grabbed the second eye w a really well choreographed hand gesture. She then smashed the fake-blood-soaked grape in her fingers at the audience with glee. (Can you tell I’m a violence choreographer by trade?)

I think I know which character you’re talking about next. From what I fondly call Shakespeare’s Slasher.