Casting Shakespeare’s Horoscope

What we can learn about early modern theatre through astrology

Technically, all forms of divination are forbidden in the Christian bible, but in Elizabethan England many chose to believe that astrology had some sort of root in what we would call ‘science,’ that it was a system of knowledge with more legitimacy than superstitious folk magic. Pre-Enlightenment, astrology and astronomy had not yet disentangled themselves, just as alchemy and chemistry still bore more than a passing resemblance to one another.

On the stage, those who believed in the promises of pseudoscience were often savagely mocked, like the dupes who become the victims of a trio of con artists in Ben Jonson’s The Alchemist (1610) or the astrologer in John Lyly’s Galatea (c. 1584-5) who falls into a pond because he’s been too busy looking up at the stars.

Nevertheless, many theatre goers and even theatre makers felt that a little guidance from the heavens couldn’t go amiss. Astrologer and occultist, Simon Forman (1552-1611) was ready to oblige.

Forman the Magician

Simon Forman was a strange and fascinating man. To some he was little more than a quack and a womaniser who exploited his patients for money and, perhaps, sexual favours. To others, he was learned occultist who offered advice using a special kind of insight attained only by a few.

Six of Forman’s casebooks survive, containing over ten thousand consultations. They form an extraordinary social record of life in London at the turn of the seventeenth century, cataloguing the deepest hopes, desires and fears of men and women from all walks of life.

The transcription of these casebooks, which you can explore here, groups common questions under headings that reveal what early modern people worried most about: ‘witchcraft,’ ‘veneral disease,’ being ‘troubled in mind,’ ‘love,’ ‘bad marriages,’ the fear that one ‘can beget no child,’ ‘trauma,’ and so on.

Forman would listen to these problems, write down key information, draw out the client’s chart and give advice. Take, for example, this haunting case of what sounds something like postpartum psychosis and CPTSD:

Agnes Olny of Tebworth in Chalgrave, 38 years. Wednesday 19 May 1602, 9.45 am. Maritus pro vxore furiosa et insanientem [the husband for his furious and insane wife]. Senseless. Has no use of her wits & light headed.

A frantic woman. Mad & laughs & misterms.

First had good motions & now worse & worse. About 3 years since delivered of a child which by means of an unskillful midwife perished & rent the woman that she ever after continued lame & could never since hold her water. Upon this day sennet about 12 of the clock she began to wax mad when Sun and Moon came both to be in Gemini & Mercury dispositer of both the lights.

Forman prescribed a prayer:

God for this sick little woman, may Satan be crushed under Christ’s feet, and may my medication be blessed, so that she may be freed from this distraction of mind and also be greatly and powerfully consoled, and with compassion and blessing.

It’s hard not to wish there was some magic in these words for Agnes.

The Shakespeare Connection

There are several significant names in Forman’s casebooks for scholars of early modern drama. Shakespeare’s landlady Mary Mountjoy consulted Forman about the whereabouts of a lost ring. Poet Emilia Lanier, who is thought by some to be the ‘Dark Lady’ of Shakespeare’s sonnets, consulted him numerous times as she sought advice for pursuing her social and creative ambitions.

Most significantly, Philip Henslowe who owned the Rose Theatre and worked with Shakespeare and many other early modern playwrights, sought help finding goods that had been stolen from his house. Forman told him that the items were buried nearby and prescribed him a charm to help pinpoint their precise location.

Perhaps it worked because Henslowe went back and consulted Forman at least once more, this time for advice on an illness. It is because of this visit that we know his age, recorded as forty two on the fifth of February 1597 which gives him a birthdate of 1555/6 and helps contextualise his career.

We sadly don’t have any records of William Shakespeare sitting down and asking to see what was written for him in the stars, but Forman certainly saw some of Shakespeare’s plays. We know this because the notes he collected on his personal life included a ‘Bocke of Plaies’ containing accounts of what he’d seen on stage. Astonishingly, the first ever eyewitness account of a performance of Macbeth – one of Shakespeare’s most magical plays – comes from this professional magician.

Forman died in 1611 after having apparently predicted his own death by drowning in the Thames, but not before he had compiled an astonishing record of life in early modern London.

Shakespeare’s Stars

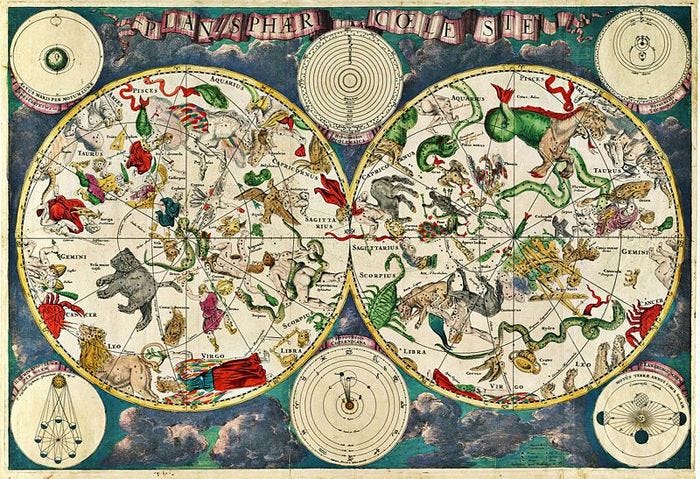

Alright, now the fun bit. The history department at the University of Warwick has produced this step-by-step guide to reading a horoscope the way it would have been read in early modern England. We’re dealing here with ‘traditional’ astrology rather than ‘modern,’ easily distinguishable because the former does not include Uranus, Neptune or Pluto which had not yet been discovered. (Incidentally, Pluto still seems to be habitually included in modern astrology, but I won’t tug too hard at that thread.)

For Elizabethans, the seven ‘dominant’ planetary forces were: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, the sun and the moon.

Annoyingly, the website Warwick suggests doesn’t let you calculate traditional dominants for birthdates earlier than 1800 and I couldn’t find an alternative site that would. For some reason they aren’t set up to retrospectively cast a future that has already happened. I did briefly consider using the 1647 guide Christian Astrology by William Lilly (an admirer of Forman) to calculate Shakespeare’s horoscope myself from scratch, but one glance at its 500+ pages of intricately-explained calculations seemed like too much of a commitment for a postscript to an article. I have a newfound admiration for the complexity of astrological chart-making if nothing else.

So I’ve cheated slightly and used the modern system to generate his ‘dominants’ at the click of a button which are apparently: Cancer, Pisces, Gemini, Pluto, Moon, and Venus. Only two of these, the moon and Venus, are counted as dominant signs in the traditional system, so I’ve then referred back to the extracts the Warwick website has selected from Christian Astrology which describes their influence in the same language Forman would have used.

Did it in any way ring true?

Well according to seventeenth century astrology, a dominant moon is apparently ‘naturally propense to flit and shift his Habitation, unstedfast, wholly caring for the present Times, Timorous, Prodigal, and easily Frighted.’ Apparently such people are particularly suited to jobs relating to water from ‘sailors’ to ‘tripe-women’ (new Whatsapp group name for me and my friends). I think we can chalk that up as a misfire.

With Venus I had a bit more luck. The individual with Venus dominant is, predictably, ‘prone to Venery,’ but is also the kind of person who delights in the pleasures of life including ‘all honest merry meetings, or Maskes and Stage-playes.’ It even lists ‘players’ (the early modern word for actors) as a favoured profession of this sign, and we know that Shakespeare was an actor as well as a playwright.

There you go then, that’s put the authorship controversies to bed!

Okay, I’ll admit that this has been a messy business. I’ve definitely taken lots of shortcuts (we don’t know Shakespeare’s time of birth, for example, though we know the probable date and location) and since there are apparently thousands of nuances to the ways in which you can plot a chart there’s no definitive version I could subject to sceptical scrutiny.

The point of this shaggy dog trip around the stars has not been to prove or disprove astrology, but to gain an insight into the popular beliefs that shaped life in Shakespeare’s London. Astrological casebooks give us extraordinary glimpses of the most intimate concerns of early modern people as this beguilingly byzantine system offered then recourse when other solutions failed.

We’ll never know whether the man who wrote the most famous plays in the world ever sat down with an astrologer like Forman. If there is any legitimacy in the practice at all, it would have made for quite the chart.

Subscribe for more articles on a range of fascinating subjects relating to magic, theatre, special effects and more. I publish my ‘horror moments’ on Thursday mornings, and other curious content like this on Monday afternoons.

Did you know that Forman has his own video game? It's DELIGHTFUL. They used his casebooks as a source of inspiration and historical grounding, although obviously liberties were taken. https://www.astrologaster.com/

I thought that Shakespeare’s actual birthday isn’t known? He was baptized April 26 and presumably born in the previous week, but the traditional date of April 23 was chosen more for ‘poetic’ reasons, namely that a) it’s his death date also and b) it’s St. George’s Day, appropriately enough for England’s greatest writer.