‘Big bad wolves of an abyssal chamber of horrors' What horror films can learn from Else Bostelmann's early pictures of the deep sea

The first person who ever depicted deep sea fish in their natural habitat was artist Else Bostelmann (1882-1961). She had been employed by American naturalist William Beebe to draw what he and fellow researcher Otis Barton described when they descended deeper than humans had ever gone before in an alarmingly tiny submarine called a ‘bathysphere.’

Beebe was a pioneer in more ways than one: his research station on Nonsuch Island, Bermuda, employed talented people from a range of disciplines regardless of race or sex. Accordingly, there were a number of women in leadership positions and Else was chosen simply because she was the best person for the job.

The task at hand was by no means straightforward. Since Else was a widow and the sole provider for a teenage daughter, it was decided that she shouldn’t take the risk of diving down in the bathysphere herself.

Instead, the observations were transmitted via crackly telephone to researcher Gloria Hollister, who would sit on the deck of the ship and quickly scribble down what she heard.

It must have been excruciating when the signal was interrupted: were the men still alive or had something gone wrong? Had the bathysphere sprung a leak and filled with water as it had done on an unmanned trial descent?

Beebe and Barton were not killed, in fact Barton went on to make a film about his adventures: Titans of the Deep (1938). Bostelmann was able to use their descriptions to recreate the things they saw.

So, what exactly did they see?

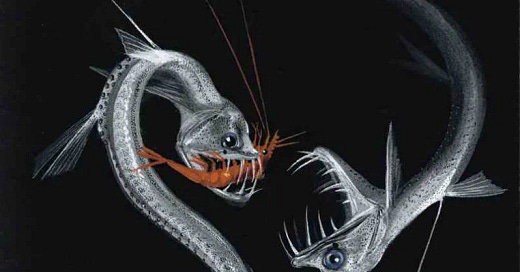

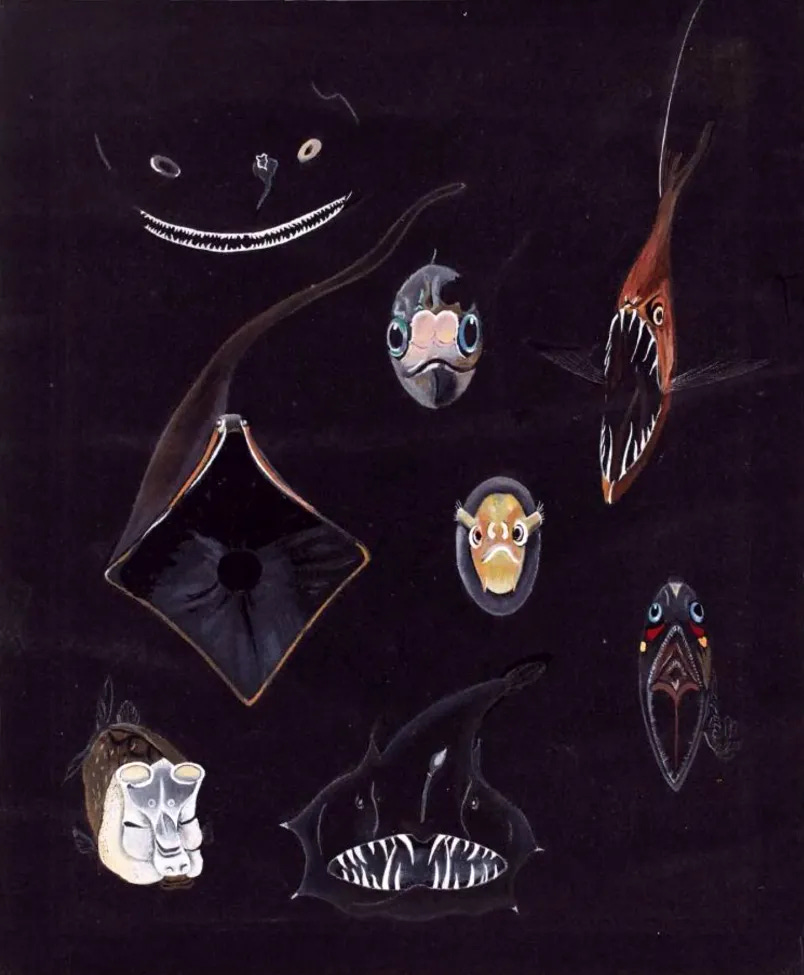

Bostelmann called the picture above ‘Big Bad Wolves of an Abyssal Chamber of Horrors.’ Not only a talented scientific artist, she had a visceral understanding of the emotive power of the world she was depicting. These weren’t just a handful of interesting new fish, this was a glimpse into an utterly alien landscape that revealed with every yawning jaw and glinting tooth how little we knew about the sea.

Every creature that appeared, by utter chance, in the beam of the bathysphere, was a hint of hundreds more still undiscovered. Whole new branches of the animal tree unfurled with the sight of a single specimen whose strange anatomy rewrote the textbooks. The darkness was the constant backdrop to this parade of revelations. Had any human beings ever stared so directly into so terrifying an abyss?

Bostelmann did draw these specimens in static detail against white backgrounds as was the norm for scientific images of natural specimens, but her innovation was to also paint them in their natural habitat, writhing, twisting, hunting, fleeing, living in the deep.

Like many a horror director would go on to do, Bostelmann composed with darkness. Her pictures plunge the viewer into the same visceral thrill of Beebe and Barton’s dangerous descent. Her use of scale, where something much larger than we might expect looms suddenly out of a total darkness, is as close to a jump scare as a single image can get.

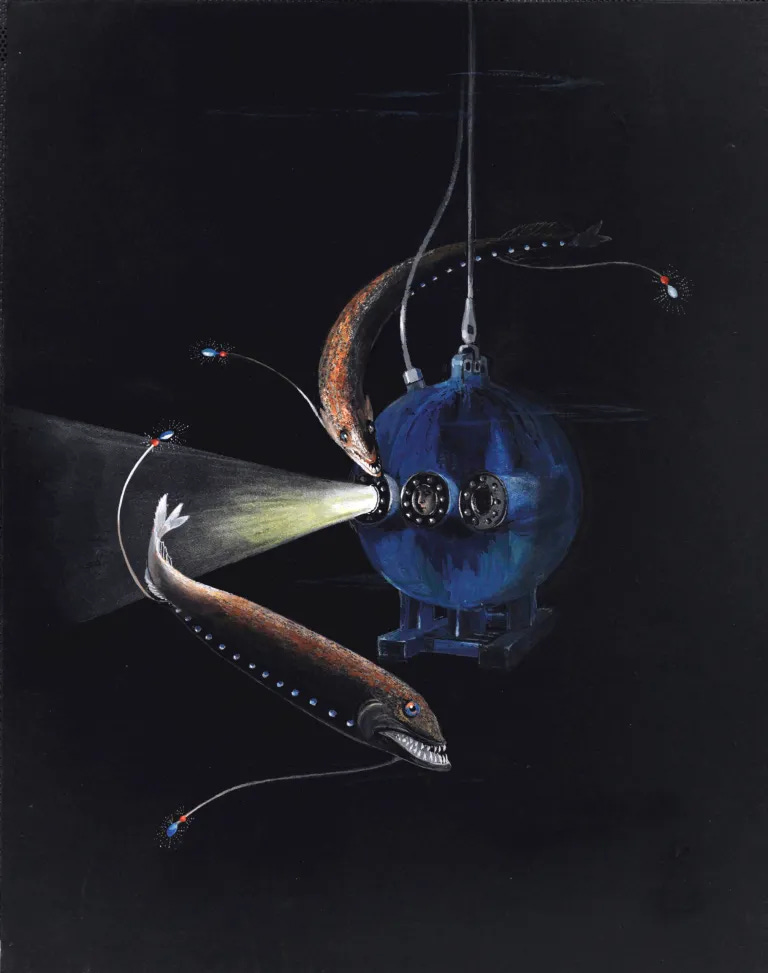

And her picture of the bathysphere itself is probably the most evocative, telling a whole horror story on its own. It sits suspended in the gloom, illuminating monsters with its single beam as a human face peeks out from a round window, vulnerable and alone, while lidless eyes and vicious teeth encircle it.

As a matter of fact, it looks extremely like this sequence from Alien (1979) when a scouting party from the spaceship Nostromo lowers themselves into the belly of an unidentified planet.

In this week’s horror moment ‘In Space, No One can Hear Gromit Scream,’ I explored the idea of spaceships becoming haunted houses and touched on the connection between them and ships or submarines which are similarly isolating and inescapable. Bostelmann’s extraordinary pictures of the deep sea are a reminder that the darkness of a natural abyss is a doubly frightening setting: scary in a literal sense because anything could be lurking in the shadows, and a stark metaphorical reminder of our ignorance.

Famously, it was Swiss artist H.R. Giger who designed much of Alien including the mysterious planet LV-246 upon which the xenomorph eggs are found. Director Ridley Scot had seen the biomechanical hellscapes of Giger’s ‘Necronomicon’ collection and hired him as a concept artist. Incidentally, the xenomorph looks not unlike a deep sea fish and is usually seen in glimpses, camouflaged in the dark.

Surely, then, the work of Else Bostelmann might also be a source of inspiration for the horror director. What is particularly affecting about her ground-breaking images, which were made famous by National Geographic and introduced humanity at large to the deep sea, is that the creatures she depicts are very real, and very much a part of our world.

If you want to find out more about Bostelmann’s drawings of the deep sea, my 10-minute audio play ‘A Song of Silent Wonders,’ commissioned by the Centre for Intercultural Musicology at Churchill College, is available to listen to here with gorgeous original music by composer Lily Blundell.

Subscribe for more articles on a range of fascinating subjects. I publish my ‘horror moments’ on Thursday mornings, and bonus content like this on Monday afternoons.

What stunning paintings!

incredible piece, but I have now discovered I might have a phobia of deep sea fish 😭