It was the age of Victorian occultism when fixation with the supernatural collided with new inventions and technologies.

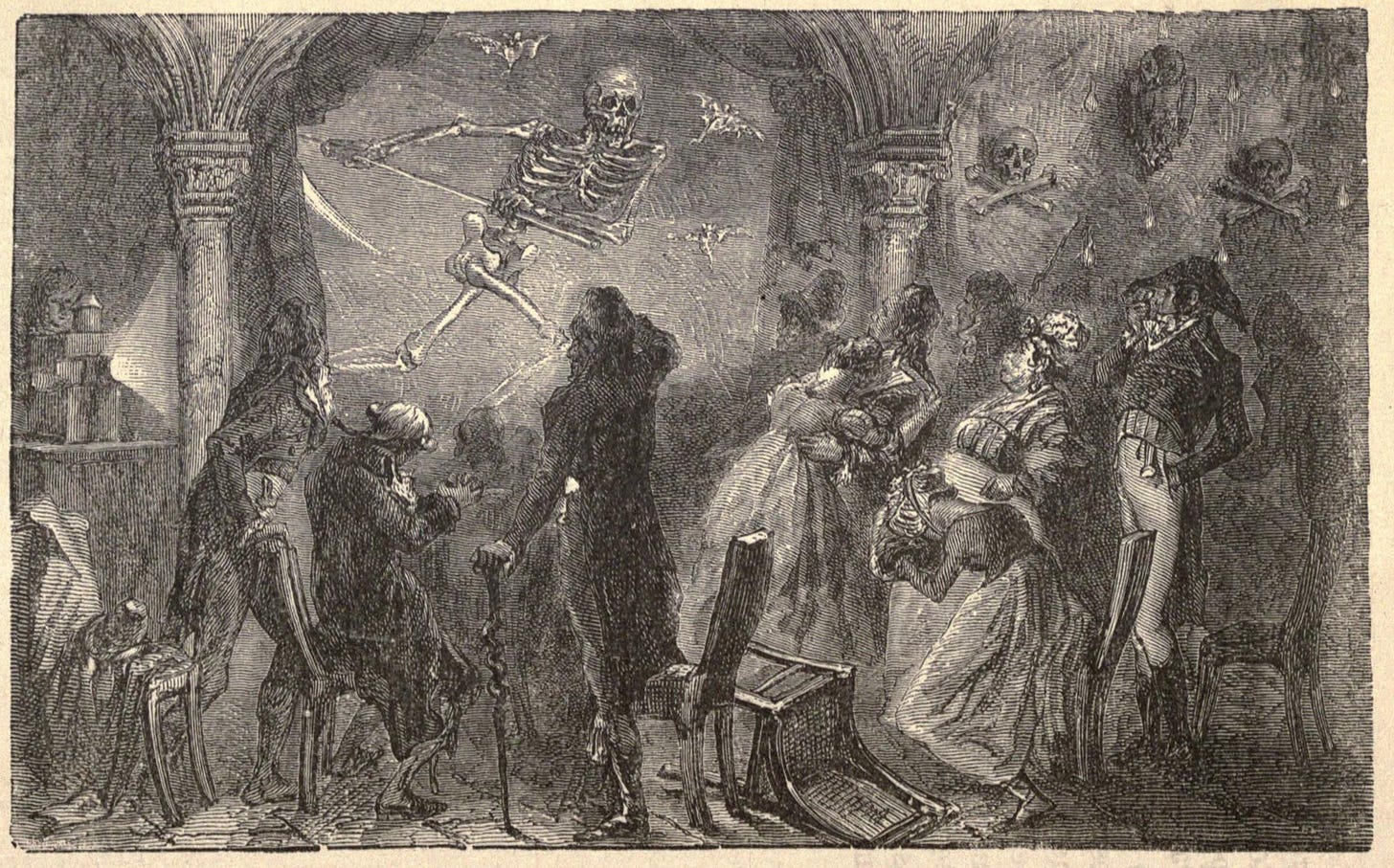

A fresh kind of theatrical enterprise was born: phantasmagoria. These shows — more interested in spectacle than story —used innovative lighting, optical effects and projection techniques to make frightening visions loom from the almost total darkness of their intimate performance space. The expression ‘smoke and mirrors’ comes from this kind of show.

As always, some practitioners were honest about the fact that this was only a form of theatre whilst others let people believe that they were genuinely conjuring spirits and speaking with the dead.

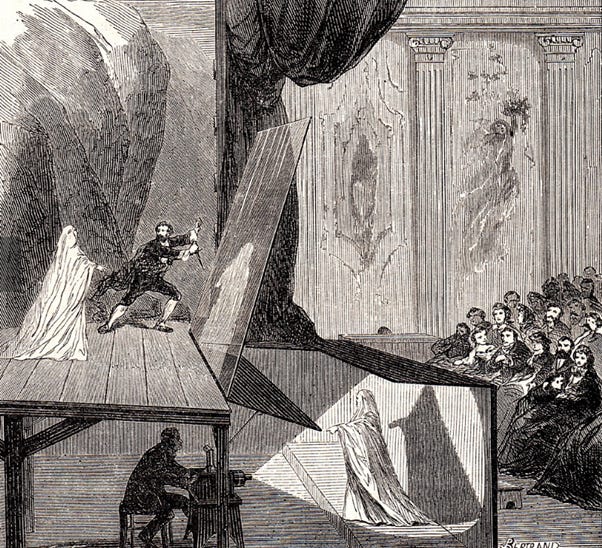

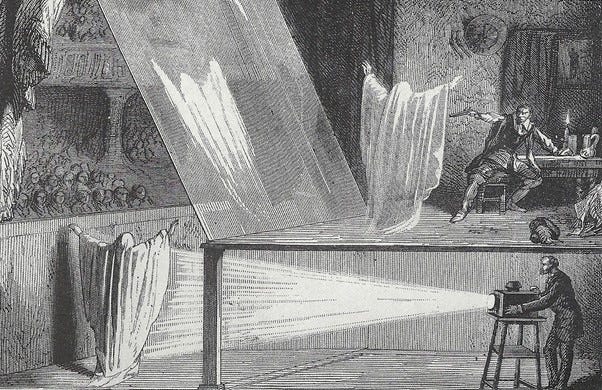

Inventor and sceptic, Henry Dircks (1806-1873) decided to expose such fakery by designing his own superior illusion. He figured out an ingenious method of making an actor appear to be transparent on stage. This, he hoped, would outshine the tricks of the mediums and educate audiences about the possibilities of new special effects. He called it the ‘Dircksian Phantasmagoria,’ but we know it today as ‘Pepper’s Ghost.’

John Henry Pepper (c. 1821-1900) was another scientist and sceptic who empathised with Dircks’ mission and worked with him on a redesign which made it easier for theatres to implement it without rebuilding their stage.

Dircks and Pepper took out a patent and the technique caught on, Charles Dickens used it in his play The Haunted Man in 1862 and it caused a sensation.

An article in The Mercury on 7th July 1879 marvelled:

“When ‘the ghost effect’ was first produced at the Royal Polytechnic Institution all sightseers were agog to behold the marvellous effects the newspapers recorded, and those of an ingenious turn of mind went again and again to try and solve the problem – including even such physicians as the late Professor Faraday – who at last had to ask for an explanation.”

Soon journalists were calling it ‘Pepper’s ghost’ to the irritation of Dircks, its first inventor. It’s unclear exactly how responsible Pepper was for this nickname, but the article from The Mercury seems to reveal why he, rather than Dircks, was remembered: as well as being a man of science, Pepper was an excellent showman:

“An apology being made for the Professor not having arrived, Professor Pepper’s well-known voice is immediately heard repudiating the idea that he ever kept an audience waiting, and with the announcement, ‘I am here!’ he is visible in the very centre of the room, and immediately walks bodily forward, down the steps towards the footlights. This would be impossible according to the arrangement of the old ghost effect – his image could appear and disappear, but his substance could not walk forth.”

Audiences loved Pepper, but Dircks was not happy. He wrote a book about how he had invented the ghost effect, pointedly refusing to mention his co-inventor by name. He saw Pepper’s adjustments as inconsequential even though, as The Mercury reported, “it was well remarked that this new arrangement is admirably adapted for dramatic requirements on the stage.”

Thirty years after Dircks’ book, The Ghost, Pepper’s own version of events was published in The True History of Pepper’s Ghost, reinstating his role in the story, though he gave Dircks full credit for the original idea.

We will never know whether the two ever reconciled. Ever eccentric, Pepper moved to Australia where he staged his own ghost stories with mixed success and attempted to invent a rainmaking device which met with ridicule and failure, dismissed, ironically, as the very kind of pseudoscience that the ghost illusion had set out to debunk.

Dircks had never been interested in the money, he had waived his right to royalties, but he did want credit for coming up with the idea. What he undervalued, perhaps, was the importance of Pepper’s role in getting the ghost in front of as many theatregoers as possible. It seems unlikely today that anyone could be fooled by a medium who used this kind of projection.

So despite their differences, the two men achieved their goal. The Dircks/Pepper ghost carried projected illusions from the hands of charlatans into the hands of storytellers. If you keep your eyes peeled you might still see their creation haunting theatres and theme parks to this day.

Here’s how you can create the technique at home with an old cassette or cd case:

Subscribe for more articles on a range of fascinating subjects relating to magic, theatre, special effects and more. I publish my ‘horror moments’ on Thursday mornings, and other curious content like this on Monday afternoons.

Oh what fun! I hadn’t thought of such in years! I knew a man growing up who built one for Halloween fun.

So interesting. Had no idea there were two inventors!