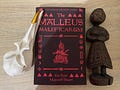

One of the perks of being a scholar with an interest in the history of magic, is that I get sent some truly weird and wonderful books. Recently, Manchester University Press asked me if I wanted an advance proof copy of Peter Maxwell-Stuart’s new edition of The Malleus Maleficarum or ‘The Hammer of Witches.’ I said yes, of course.

The Malleus was originally published in 1487 by Heinrich Kramer also called ‘Henricus Institor’ or more commonly, ‘Institoris,’ a German churchman who was extremely worried about the terrible threat of witchcraft. His ‘Hammer of Witches’ explored how to identify and prosecute people who used magic to do harm. Like many instructional and philosophical books from the period, it was constructed in the form of questions and answers with the reader assuming the role of the student in the exchange.

In part 1, Institoris establishes that harmful magic is real, that it’s on the rise, and that women are particularly susceptible to becoming agents of the devil. Women are ‘more given to fleshly lusts’ than men ‘as is clear from her many acts of carnal filthiness.’ He uses the story of Genesis, where Eve was supposedly shaped from Adam’s rib, as proof that women are fundamentally curved or warped in nature: ‘since she is an unfinished animal, she is always being deceptive.’

Institoris imagines that women are tempted to have carnal relations with demonic spirits to assuage their constant desire for intercourse. The mouth of the womb, he explains, is a thing ‘which never says “enough.’” Especially bizarre to the modern reader is his claim that witches have the power to make men think their penises have been removed from their bodies – they can’t actually steal them, he hastens to clarify, but the effect of the trick can be just as damaging as if the victim really had been emasculated.

Midwives are literally demonised as Institoris claims that witches ingratiate themselves with other women in this way, intending to cause harm to infants. Apparently, witches he had questioned admitted ‘no one does more harm to the Catholic faith than midwives. When they don’t kill the children, they take the babies out of the room, as though they are going to do something out of doors, lift them up in the air, and offer them to evil spirits.’ They have been known, he says, to devour children and drink their blood.

In part 2 we get more of the same – one of the great things about Maxwell-Stuart’s edition is that he mercifully summarises Institoris’ most rambling and repetitive passages. We get anecdotes to prove points made in part 1 including a horrifyingly graphic story of domestic violence to accompany the earlier discussion of penis-vanishing. A young man from Ravensburg, believing a former lover had enchanted his penis away:

…assaulted her, wound a towel tightly round her neck, choked her [with it], and said ‘If you don’t make me whole again, you’ll die at my hands.’ The woman was unable to cry out. Her face swelled and started to turn black. Then she said ‘Let me go and I’ll cure you.’ The young man loosened the knot and made [the towel] less tight, and the witch touched him with her hand between his thighs or hips, saying, ‘Now you have what you want.’ The young man, as he said afterwards, had the remarkable feeling, before he checked himself by looking or touching, that his penis had been restored to him merely by the witch’s touch.

To Institoris, this obvious case of a woman playing along with a man’s delusion to stop him killing her is to be taken at face value: proof of her demonic power. If the modern reader is beginning to lose their sense of humour about the Malleus in part 2, part 3 is where it reaches a chilling conclusion that snuffs out the desire to mock.

The chapter titles alone now bear witness to the cruelty of the text: ‘should the woman be told the names of her accusers?’ ‘how she should be tortured the first day’ ‘can one promise to save her life?’ It is here that we remember that this isn’t just a man describing something laughably hateful he believes about women, this is a man calling for his fellow human beings to be tortured and killed for crimes that are impossible – but there’s a happy ending to this sorry tale (sort of).

Heinrich Kramer wrote the Malleus in part because he was frustrated by the complacency of courts and lawmakers on the subject of witch hunts. He is trying to convince the men in power to side with him on the subject precisely because he had so dismally failed to do so in the past.

Marion Gibson tells the story best in Witchcraft: A History in Thirteen Trials which I’ll be reviewing next month. The first chapter of her book brings to life the case of Helena Scheuberin, an Austrian woman who, in 1485, was accused of witchcraft by Institoris after she made fun of his sermons. Scheuberin managed to save herself and six other women who were co-accused, by refusing to confess and drawing attention to his lurid fixation with her sex life. A medieval courtroom full of men sided wholly with the women and eventually the bishop of that region asked Institoris to leave Innsbruck entirely.

And thus, the embittered ‘Hammer of Witches’ was composed. Whilst it wasn’t adopted and accepted in its day as widely as Institoris hoped, it had an unpleasant afterlife over a hundred years later. During the English civil war, Matthew Hopkins would style himself as the ‘Witchfinder General’ and take up Institoris’ mission, leading to the deaths of between 100-300 people… but that’s a story for another day.

Interestingly, Peter Maxwell-Stuart offers a caution in his new edition to attempts to psychoanalyse and thus condemn Institoris as a man defined by unusual woman-hate and paranoia, making the careful point that ‘Institoris was no more misogynistic than any other writer of his period… his animus against women was driven by contemporary physiological theory about their insatiable sexual appetite which gave an easy access to Satan and his evil spirits.’ He also points out that the other witch trials where Institoris had learned his craft had similarly singled out women: we can’t, perhaps, say anything too definite about personal motivations.

Gibson is more critical of Institoris himself, pointing out how many men in positions of power disliked and opposed him, particularly Scheuberin’s ‘hot-shot lawyer’ Lord Johann of Wemding who tore into Institoris for his disregard for proper legal procedure in the manner in which he had conducted his case against the women of Innsbruck.

Gibson suggests that it was precisely because Helena Scheuberin had been such a compelling witness in her own defence and had stood up to him so admirably when he questioned her that he added to the Malleus the instruction that there was no need for ‘the screeching and posturing of a courtroom’ when trying a witch and that torture should be applied immediately upon arrest to guarantee a confession. This suggests, perhaps, that he was personally frustrated by the women’s ability to win the support of other men and wanted them questioned behind closed doors. Whether this book was more misogynistic than other texts of the period remains somewhat moot. That misogyny fuelled attitudes towards witchcraft is certain, and Institoris added plenty of fuel to that terrible fire.

Maxwell-Stuart’s new edition looks a bit like a grimoire but, ironically, this is a far more dangerous book than any of the tomes of magic I’ve come across in my research. I’m not aware of any particular evidence of murders being committed because someone used elaborate ritual magic to try to divine the future or find buried treasure, but innocent women and men did end up dying because of the Malleus and unlike any grimoire I’ve come across, it was designed to promote the torture and execution of women.

Reading a book like Malleus Maleficarum is a bit like studying a poison in hopes of finding a cure. If you’re interested in the history of prejudice and persecution, this is a vital read and the new editions casts fascinating light on its cultural context and impact– but maybe line up something comforting to restore your faith in people as an antidote. For me, a good go-to is always Oliver Postgate films. They work quite well for hangovers too.

So I’m off to watch Bagpuss, bye for now!

Subscribe for more articles on a range of fascinating subjects. I publish my ‘horror moments’ on Thursday mornings, and other curious content like this on Monday afternoons.

This guy sounds like he was an incel of his time, and instead of picking up a hobby he decided to write a book about how to kill witches.

Maybe his mum just didn't hug him enough?

Great read, as always!